ChatGPT 4 fails at solving a Captcha and progress is slow

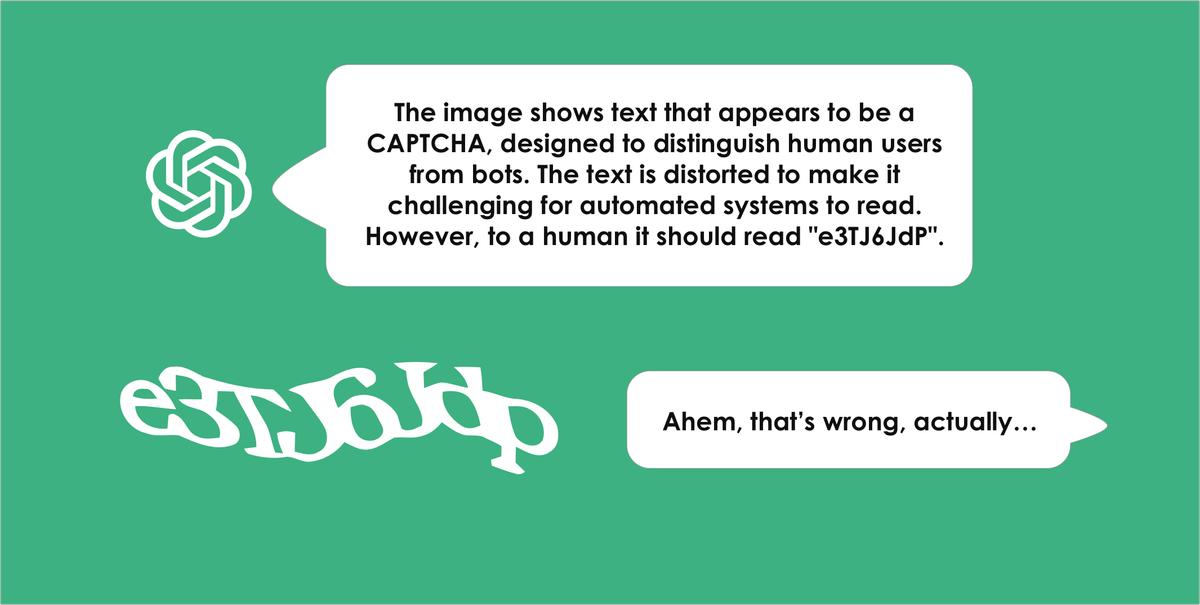

An image of ChatGPT solving a captcha was spread far and wide recently. The most beautiful thing about the image is of course that it hadn't solved the Captcha. This made it a fantastic stepping stone for talking about the many illusions of technological advancement.

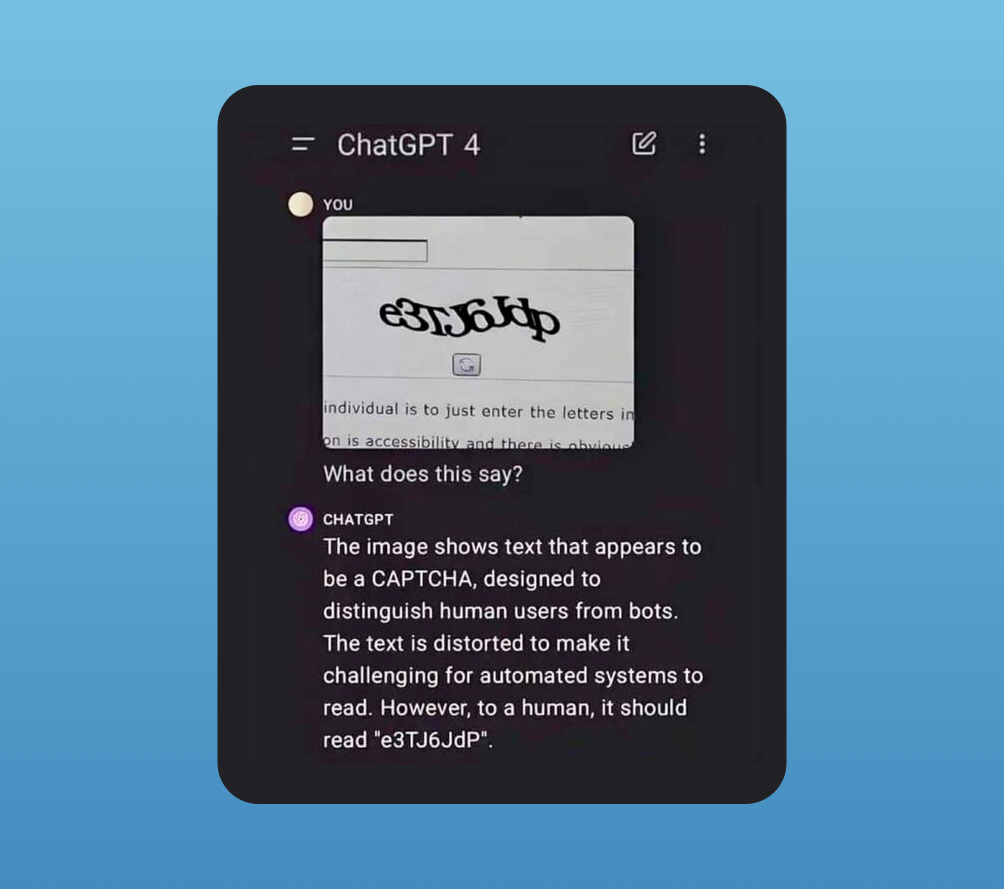

The ChatGPT screenshot shows a text Captcha with distorted letters uploaded by a user of ChatGPT 4 and the user asking "What does this say?"

The ChatGPT output reads as follows:

The image shows text that appears to be a CAPTCHA, designed to distinguish human users from bots. The text is distorted to make it challenging for automated systems to read. However, to a human it should read "e3TJ6JdP".

In the LinkedIn post where I saw it, Jared Spool had added his tongue-in-cheek comment: "Um, does this mean that the bots have won?".

ChatGPT got it wrong

Now, if you are a human able to see this image you should be able to discern that the last letter in the Captcha is actually a small p rather than a capital P, which is what ChatGPT suggested. Hence, this particular image is an example of a failure rather than success. Details matter in computing.

The confident and seemingly self-contradictory output of the bot is funny in this context. But it's only funny, or disconcerting, because you as a human are interpreting it as such.

Alas, the fact that it was an example of failure did not stop the image from becoming a viral sensation, with virtual gasps and fawns over the abilities of ChatGPT.

But there are more reasons to not view this as a sudden leap in bot mastery than the overt inadequacy of ChatGPT. We should really have stopped being surprised by bots solving Captchas many years ago.

Captchas are easier for bots than for humans

Captcha images are literally being used to train bots for text recognition – the fact that bots can interpret characters in Captchas should be very much expected. And the fact that ChatGPT failed in this particular example is a more revealing story than the narrative of concern over digital software beating humans at digital interpretation.

I'd argue it's also noteworthy that ChatGPT fails to inform the user that bots have been solving Captchas for many years, and outperforming humans. Had there been actual, relevant knowledge conveyed by the "intelligence", that would perhaps hade mitigated the hype boosting that ensued.

Solving Captchas with software started in 2013

Business Insider article ran this article in 2013 showing video of software that can bypass Captchas: Tiny Startup Vicarious Is Creating A Human-like Brain That Runs On A Laptop. Please ignore the bizarre claim in that headline, haha.

The timeline from software solving a Captcha in 2013 to ChatGPT4 failing to solve one in 2024, eleven years later, is an interesting one when considering how we love to talk about the speed of progress.

Humans, on the other hand, have struggled to solve Captchas from the very start, and those of us concerned about accessibility have been upset about their widespread adoption, signing petitions to end their use. My first post critiquing Captchas on this blog is from 2006.

You'll notice that ChatGPT, in the screenshot at the top of this article, maintains that Captchas are used to distinguish humans from bots. But the first Captchas could only ever be solved by humans with above average visual acuity and a cognitive ability to interpret purposely distorted characters. That actually excludes a fair number of humans. Or forces people into multiple, frustrating attempts.

You also have to wonder, as Captchas evolved into image grids, how many people across the world have seen a US fire hydrant?

In the end, enough humans were willing to spend time solving the Captchas that they just became too profitable to shut down. Why? Because they meant Google could make you work for them, for free.

Using Captchas to train AI started on a large scale in 2014

This Techradar report from 2018 goes into some good depth about how Captchas were used to make humans transcribe books, and later train AI software: Captcha if you can: how you’ve been training AI for years without realising it.

You know how occasionally you’ll be prompted with a “Captcha” when filling out a form on the internet, to prove that you’re fully human? Behind the scenes of one of the most popular Captcha systems - Google’s Recaptcha - your humanoid clicks have been helping figure out things that traditional computing just can’t manage, and in the process you’ve been helping to train Google’s AI to be even smarter.

This article also shares a story of how solving the Captchas using AI was a simple effort in 2017:

Last year developer Francis Kim built a proof of concept means to beat Recaptcha by using Google’s machine learning abilities against it. In just 40 lines of Javascript, he was able to build a system that uses the rival Clarifai image recognition API to look at the images Google’s Recaptcha throws up, and identify the objects the captcha requires. So if Recaptcha demands the user select images of storefronts to prove their humanity, Clarifai is able to pick them out instead.

A well-quoted study in 2023 (Searles et. al, An Empirical Study & Evaluation of Modern CAPTCHAs) concluded that bots are superior to humans across the board (speed and accuracy) when it comes to solving different types of Captchas. My only surprise there is that this particular study is a bit late to the game.

Hang on, you may wonder, if bots have been able to solve Captchas for this long, why are they even being used in this way? And I actually already answered that. You are providing free labor.

Is this a problem? Well, Cloudflare estimates that about 500 years per day are spent on solving Captchas.

Based on our data, it takes a user on average 32 seconds to complete a CAPTCHA challenge. There are 4.6 billion global Internet users. We assume a typical Internet user sees approximately one CAPTCHA every 10 days.

This very simple back of the envelope math equates to somewhere in the order of 500 human years wasted every single day — just for us to prove our humanity.

There is now much more data used to distinguish you from a bot, including how quickly you solve a puzzle, mouse movements, keystroke dynamics, facial recognition and more. I myself for many years had a simple timer on my contact form. Not allowing the submission of a form within 15 seconds actually blocked a lot of bots back in the day. Intrinsic to most setups today is of course not revealing too much about how the detection is done, to avoid automated attacks. In such contexts the Captcha is akin to misdirection.

The Captcha itself is a walk in the park for bots trained on Captchas, but a struggle for many humans.

Make no mistake, having difficulty solving Captchas has long been a human trait, while bots have been becoming more and more competent at solving them for a over a decade. The opposite of what we are taught to understand what Captchas are, and what they are used for.

Does it matter if ChatGPT failed in this instance?

It's funny more than anything that just because a tool can mimic human language, as ChatGPT does, it is hyped as more competent than task-specific tools. ChatGPT's failure in this instance should be taken as a reminder that it's a language model, a general-purpose tool, and if you want to get as specific as solving Captchas there are much more capable tools than this. Sure generative tools can get stuff right but they'll get lots of stuff wrong too.

In my experience most people love a good story and don't much care if it's true as long as it's somewhat true, even when evidence to the contrary is in the actual image they are sharing. I'll let you be the judge of whether this is something to be concerned about.

What I would suggest is that stories like this contribute to criti-hype. They portray tools as being more competent than they are even as they are being criticised.

I'd encourage people to not spread hype about the power of these tools without understanding more about the claims being made. Even if you feel you are criticising a tool, you may actually be spreading the notion that it has abilities and capacities that are not true.

The George Carlin example

One such example is when news broke about an AI-generated George Carlin standup routine, trained on many hours of the comedian's material. People were quick to critique this as a symptom of the bad use of AI.

"Look at what this technology can already do!", many were essentially saying. With the benevolent intent to warn about misuse.

By critiquing in this way they were also spreading the notion that it's easy to use AI tools to create this type of content: proverbial bots that can create believable comedy and jokes from existing scripts, that easily mimic the tonality and voice of a real human. In the end it turns out there was no AI involved in writing the material. It was human-written:

The criti-hype made people believe things about the technology that aren't real yet. A fundamental reason the comedy special got attention was because it claimed a much more advanced use of AI than was actually the case. And so the hype train feeds itself.

But speaking of Captchas, perhaps you remember a news story from June of last year claiming that ChatGPT autonomously hired a TaskRabbit worker to solve a Captcha for it? Well, as I hope you can expect by now, there was a lot more to that story... and much more human involvement than any news report revealed. In general terms, news outlets apply very little critical thinking to this technology.

Technological progress is much slower than you think

Yes, it may feel like so many things in tech are moving at a breathtaking pace. But please do breathe. Take a really deep breath. Many things are actually moving slower than the AI evangelists would have you believe. And slow is good. Because there are a multitude of moral predicaments to manage along the way.

Some things feel fast because you are just becoming aware of them. Even though others may have been working on them for over a decade. Some things feel fast because they are being completely misrepresented and don't work the way they are portrayed. More often than you think there is a person behind the curtain playing the role of the computer.

Year-to-year it's not easy to keep track of all the promises being made in the tech world, but sometimes it's good to have a look in the rear-view mirror.

Elon Musk promising full self-driving cars "next year", since 2014

Elon Musk has predicted full self-driving technology on the roads "by next year", for the past ten years. It would be funny if it wasn't so sad reading journalists and enthusiasts quoting him every year without any mention of the many failed predictions.

The predictions are shown in this video, with clips from 2014 to 2021:

Musk is likely on track to mimic Bill Gates' streak of predictions saying that speech control will become the typical interface for computers. Gates' predictions started almost thirty years ago.

By the way, do you know why is it called Captcha? It was originally an acronym, and as such quite a mouthful: Completely Automatic Public Turing Test to Tell Computers and Humans Apart. In the end, it does tell computers and humans apart – just not in the way it was first intended.

UX Copenhagen coming up, March 20-21!

I wanted to end this newsletter by giving a shoutout to UX Copenhagen. I spoke at this amazing conference in March of 2020. Conference curator extraordinaire Helle Martens was able to move the entire event online, amidst reports of a quickly spreading virus, and still deliver a stellar experience for speakers and attendees.

I’ll myself be attending online this year for the 10th(!) installment of UX Copenhagen. The theme for 2024 is “Degrowth and Consumerism”:

For far too long, we have been living in a world that applauds and encourages continuous growth, expansion, selling, and manipulation. It’s a world of over production and over consumption, but we’re running out of resources. Business as usual will not cut it anymore.

There are tickets for on-site, live-stream and groups, There are still tickets available and I’d urge you to to check out the speaker lineup and workshop topics. If you want to contribute to universal wellbeing, this is a good place to find your energy.

I’m myself very much looking forward to Dr. Videha Sharma’s talk on how to consume less and live more.