Avoiding data collection on the internet is a challenge. In a recent experiment with online anonymity, I withdrew cash to pay for a coupon that would allow me to sign up for Mullvad VPN. I even wore a baseball hat to more easily obscure my face. One of the few VPN providers to encourage this, I can use their service – and pay for it – without giving away my identity.

Mullvad* VPN have the right idea. The less data they collect about me, the less concern they need to have for any data collection leading to potentially harmful outcomes.

*"Mullvad" is the Swedish word for the burrowing mammal known as mole.

Worryingly, it appears harder and harder to build an online presence without also subjecting customers and stakeholders to extensive tracking. Just by your choice of platform you could be forcing them into a system of surveillance without any proportionate benefit to your own organisation.

"Come play with us over here. Don't mind the cameras, they're not ours."

In a world of commercial interest some would argue that we to some extent must accept this circumstance. (Mullvad and myself beg to differ.) But what happens when organisations with an expressed intent to protect their members set loose the same trackers?

A 2021 report from The Markup showed how non-profit websites are riddled with ad trackers. And in their own look at non-profit websites, the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) recently noticed the same patterns of behavior, emphasising how people are again and again being harmed by data collection.

Choosing to collect the data of supporters, clients and visitors isn’t just a marketing, monetary or ideological decision: it’s a decision that puts people in danger. In a post-Roe world, for example, law enforcement might use internet search histories, online purchases, tracked locations, and other parts of a person’s digital trail as evidence of criminal intent – indeed, they already have.

So yes, the rather alarming effect can be that non-profit organisations, knowingly or unknowingly, put at risk the same people they are trying to support.

If you do want to start caring better for the privacy of your members, supporters (and clients!) the EFF has a guide for better online privacy practices. It's targeted towards non-profits but, as you may well expect, I of course encourage everyone to read it and ensure these topics of concern are being managed with intent and transparency. Not casually dismissed or ignored.

Be kind and let go of that data,

Per

My latest posts

- How to build the good and responsible thing @ #frontzurich. I had a really good time at the Front Conference in Zürich, with fantastic feedback on my talk, great conversations, mindblowing inspiration and the opportunity to stay up late with a thoughful gang of people. My slides are here, with lots of links, and the recording of the talk will likely be published next year.

- A guide to voting in the Swedish election. While the election is now formally over, this post gives some insight into the types of content I like to produce to help people act on their rights to influence the wellbeing of themselves and their communities. I've been very moved by the people reaching out to thank me for the website.

News wrapup

- TIME: The Twitter Whistleblower Needs You to Trust Him (TIME). A deeper look at Peiter "Mudge" Zatko's insider criticism of Twitter security issues and moral weaknesses. What he gets right and what he gets wrong.

- The New York Times: A Dad Took Photos of His Naked Toddler for the Doctor. Google Flagged Him as a Criminal.

- Salon: Understanding "longtermism": Why this suddenly influential philosophy is so toxic

- Mashable: It took just one weekend for Meta's new AI Chatbot to become racist. At least it's not sentient.

- People vs Bigtech: A 10-point plan to address our information crisis. Presented by 2021 Nobel Peace Prize laureates Maria Ressa and Dmitry Muratov at the Freedom of Expression Conference, Nobel Peace Center, Oslo 2 September 2022

- The Markup: Does Your Car Need to Know Your Heart Rate?

- The Verge: This site exposes the creepy things in-app browsers from TikTok and Instagram might track. Did you know you’re potentially being tracked when you load an in-app browser on iOS?

- Input: How one TikToker convinced folks he was an AI-generated character. “The goal was never to trick people,” creator Curt Skelton tells Input. “They did that to themselves.”

- EFF: Nonprofit Websites Are Full of Trackers. That Should Change.

Thoughtful read on AI complexities

In this article we learn about the pre-digital history of determining who gets a kidney transplant, how algorithms get it wrong and the importance of including the community in decisions that impact the community.

The first plan for the new system, unveiled at a public meeting in Dallas in 2007, was to maximize the number of life-years saved by the available organs. That’s an idea that makes a lot of sense to doctors. But it would likely also have meant more organs for younger, wealthier, and whiter patients—worsening racial disparities and hurting patients who’d waited the longest. The designers of this first plan were honest about its faults. They even showed a chart that vividly depicted how the plan would shift transplants away from older patients, toward younger ones.

Read The Kidney Transplant Algorithm’s Surprising Lessons for Ethical A.I.

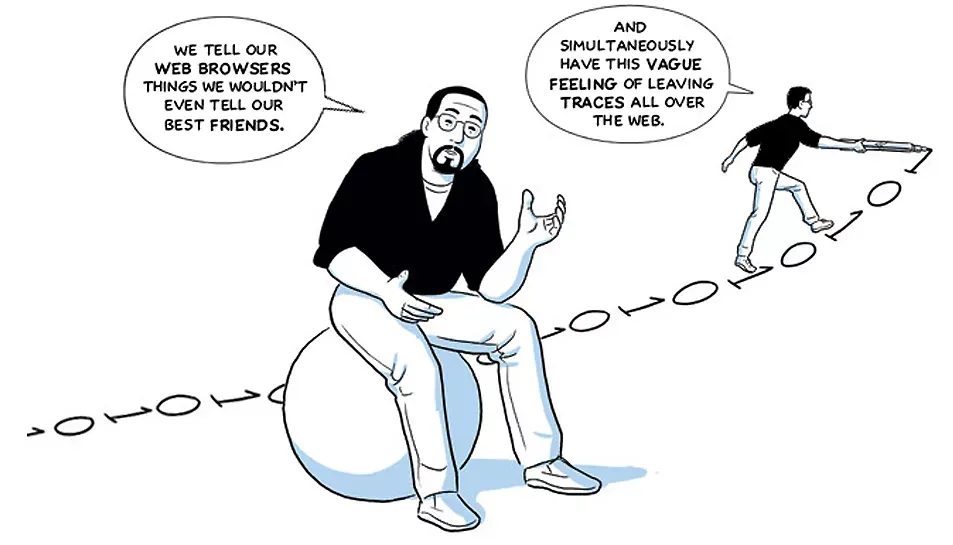

A cartoon about all the things Chrome collects about you

The multi-page Contra Chrome comic is drawn by Leah Elliott, an artist and digital rights activist. You can follow Leah on Mastodon.

With her meticulous rearrangement of Scott McCloud‘s Google-commissioned Chrome comic from 2008, she delivers what she calls "a much-needed update". Laying bare the inner workings of the controversial browser, she creates the ultimate guide to one of the world‘s most widely used surveillance tools: Google Chrome, which – by design – is all about you.

Why this strikes a chord with me: Not long ago I helped a friend who was leaving their partner under distressing circumstances. Together we found their online searches stored in account history, available for their partner to read as they shared passwords with each other. Things they had assumed were private actions – and thoughts – were far from it. Instead these thoughts were recorded and stored, becoming potential triggers for harm.

Recommended newsletter

Lauren Celenza is an independent UX designer, writer, and educator based in Seattle. Lauren teaches design and ethics at Harbour.Space University in Barcelona and Bangkok and writes the newsletter How to Work in Tech Without Losing Your Soul.

Member discussion