Digital abuse is hard to leave – by design

Once we recognise digital harm as a form of abuse it becomes clear how the same patterns of victim-blaming that we see in all abusive relationships tend to be repeated.

One of the most common rebuttals I hear when talking about harmful design is the idea that "people can just leave if they don't like it". This follows a similar pattern to all abusive relationships where one party is exerting power over a trapped victim. To outsiders without personal experience, just opening the door and walking out – or clicking "delete account" – may seem deceptively simple.

Thankfully, there is now extensive research telling us why people do not leave abusive relationships, research we can choose to learn from. Alarmingly, it appears that this same knowledge is also used to trap users of digital services and design is used consciously to make leaving more difficult.

We need to tread carefully here. In domestic violence cases there are many additional fears around leaving such as homelessness, threats of more violence and lack of family or community support. The issues I bring forth here are ones that have clear-cut parallels in digital relationships. Context matters, and we would be foolish not to acknowledge the dangers of these counterparts.

1. Society normalises unhealthy behaviour so people may not understand that their relationship is abusive.

We live in a world where:

- the commercial norm is to collect data about users and exploit this for profit.

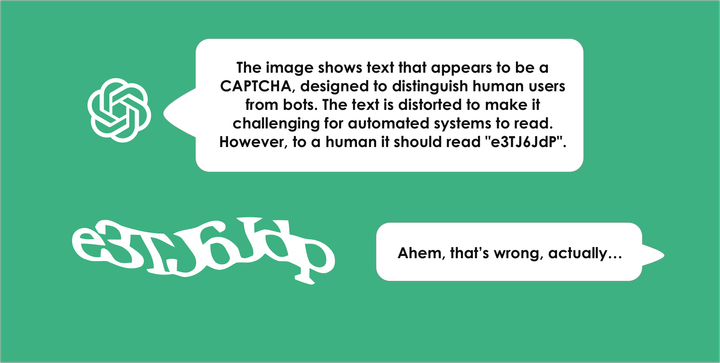

- companies hide (by intent or by normalization) important information in extensive terms and privacy policies that are hard to read, hard to remember, and most often: not read at all.

- a majority of actors are trying to tie consumers up in long-term subscriptions.

- designers learn about habit-forming techniques to influence people one way or the other.

- it's expected to be harder to leave a service than to join it.

If these actions and circumstances are so widespread, many people assume they must have been vetted and accepted – so they accept them as inevitable. While people with time and money may manage these issues with some ease, that is far from true for everybody. If you for example have cognitive or financial obstacles, your ability and capacity for managing (or questioning) these norms is impaired.

2. Victims feel personally responsible for the abusive behavior.

With the common expectation of making rational choices and the way society blames people for poor choices, the victims also adopt the mindset of blaming themselves.

- "I bought the wrong thing, but that’s likely just me."

- "I signed up for that trial period but it’s my own fault I’m now stuck in a 12-month contract."

- "I can’t seem to stop checking notifications but that’s only my own lack of self-control."

- "They used my Instagram photo of a rape threat in widespread advertisement but it’s my fault for not reading the terms of service."

- "Wow I’m so bad at computers I’m sure everyone must be laughing at me behind my back."

It is obviously never your own fault when you are betrayed and taken advantage of. It's not your fault for not understanding the mechanics of the digital world. But when we see other people in our life coping (or appear to be coping) with similar challenges, even when their conditions are very different, we often conclude that we ourselves must be the problem.

3. If you stick it out, things might change.

People don't fall in love with abuse, they fall in love with all the good feelings and benefits that a relationship brings. The awareness of abuse, and its extent, tends to increase over time.

In other words: You’ve had good times together, there is always a possibility that things could get a lot better. The abuser might come to their senses and treat you better. There are certainly things you would miss – it's not like you think about the abuse every day. You still enjoy many of the benefits.

And now that the media is writing about more of the harm, many hope that these businesses will listen and start treating everyone better. Without an awareness of the underlying reason for the abuse (in the digital world it can be as simple as a business model) there is always hope that the relationship will improve at some point in the future.

4. You share a life together.

This issue hits very close to home as a designer. As part of many teachings around behavior and design, it is recommended that one lets the users invest time, effort and emotion in a service. We do this by having them for example upload pictures, change colors and set profile pictures. The more a person invests in this “life together”, the less likely it is that they will want to abandon it, even when you treat them poorly, even when the relationship begins to resemble abuse.

As a design strategy, having people contribute personally is extremely powerful, which is why it also carries an an enormous potential for harm. A person who invests must also be allowed to leave with their belongings. This is one reason the ability to export your own data is a central part of GDPR.

5. Leaving is made difficult

I’m confident there are many of us who have experienced the ease with which we sign up for services, as well as the obstacles erected to prevent us from leaving. Here in Sweden the most common example is signing up for phone and tv contracts online in mere seconds, but then requiring any cancellation to be made by phone, where queues are inevitable.

Facebook, when you go through the many steps of canceling your account, throws up the faces of your friends and family - claiming in large letters that they will "miss you!". This is not only abuse of the user trying to leave, but of the human beings who have not given consent for their faces to be used as hostage keepers.

Your role-related responsibility as a designer

Once we adopt a mindset where we allow profit to come at the expense of human wellbeing we are enforcing an abusive relationship. If you as a designer are concerned about the wellbeing of others, you need to learn how to recognise these harms.

In my teachings around digital ethics I talk about the consideration that must come before, during and after the development of new technology and its features. To claim benevolence as creators of digital tools we need to:

- Understand our own value systems and the outcomes we want to avoid. The problem areas of technology are broad and far-reaching. By being aware of them and regularly discussing them we are in a better position to avoid repeating the mistakes of others.

- In early stages consider not only the use and users of a tool, but the non-users and the co-dependent users. When it makes sense I favor the word participants over users, such as in The Inclusive Panda model. You can also be helped by second and third order thinking, as well as speculative design and imagining different futures.

- Complement performance indicators with indicators of wellbeing: such as autonomy and the ability to influence, control and grow. Allowing people these abilities can become part of a regular assessment, and is something a person in your team can be appointed to manage.

- Provide feedback mechanisms that allow the discovery of harmful outcomes that a homogenous team can not discover on its own. Preferably by also proactively engaging with diverse groups of people to listen to as many perspectives as possible.

Anything we create will have an impact. A big part of your job will be to understand that impact – through speculative tools, risk analysis and listening – and make transparent decisions that mitigate and avoid harm.

Impact management is not obvious, apparent or easy. But making time for it is always the right thing to do.

Your personal choice

I personally have left Facebook. This was by no means a simple endeavor, even for a privileged person like myself. The want to do it was simple, but the follow-through is difficult, for all the reasons I've mentioned above. This is why I do not judge people who do not leave these platforms. I can only offer awareness of the possibility of doing it, and support for the action, but the choice is always personal. It's okay for me in these instances that individuals make the judgment call that a service harming them or others, is worth the benefit. I do, however, always encourage people to spend time regularly reflecting on their own wellbeing – as well as the wellbeing of others.

Also read: 11 reasons why people in abusive relationships can't just leave (One Love Foundation).

If you want to learn more about how technology is used to enable domestic abuse, you should follow the work of Eva Penzeymoog and the Inlusive Safety Project. [update: also see her new book: Design For Safety.]

Comment