My talk from UX Copenhagen earlier this year – First, design no harm – is now online. It’s an emotional talk that takes its start in a story of abuse and the systems that support that abuse. As designers we have the power to abuse, but how aware are we of when this happens?

Find the transcript of my talk below the video. You can also access my conference slides and my first blog post on this topic.

Transcript of the talk First, Design No Harm

This year it’s exactly 30 years ago since I started high school in Sweden, at a boarding school where I lived in a dorm with 25 other boys aged 14-19. Only one month into this experience I found myself standing in line for breakfast in the dining room, and there was a lot of commotion and nervous laughing going on.

The reason for this was that during the night four of the last-year students had barged into the rooms of three first-year students, pinned them down on their beds, stripped off their underwear and shaved off their pubic hair.

This had been a spontaneous hazing ritual wherein young students are welcomed into the brotherhood of the dorm. While this was perhaps one of the more severe happenings, these rituals were not uncommon and often involved physical harassment and embarrassment of a sexual nature.

Upon leaving the school it took me several years to stop defending these practices and recognise how wrong they are. And it was only a few years ago I last saw parents on TV, mothers, still defending how these behaviours are part of the activities that build character and friendship.

After many years of reflection I have boiled down my own and others’ unwillingness to admit how vile the activities in fact are, to this simple truth:

If I admit that it was a situation of abuse then I would be forced to myself reconcile with the idea of being a bad person.

Unsurprisingly, most of us resist doing this.

Sometimes I would tell myself that at least I did not physically harm people, but when I’ve revisited my own behaviour I was able to see how this was not about individual events, but about a systemic behaviour that I of course played a part in.

I was a child. But I assumed the environment I was in to be my identity. I assumed the people in my vicinity to be my community. And I adopted the rules and mindset of this community.

I did intervene in the beginning. I was one of several people who leaked to the press what had happened. After media attention, the four perpetrators were expelled one month before their graduation.

You might think of this as justice served but that is only if you fail to consider how those three young men had themselves been abused, at the same school, since the age of 14.

As more and more people find themselves defending unethical practices in design I hear CEO’s, managers, design leaders and people in behavioural economics profess some variant of this statement:

If you screw people over they are going to stop doing business with you, and they’ll tell all their friends to stop doing business with you.

Essentially, if you abuse people, they will leave. And, if they have friends, they will tell all of them. I believe it’s fair to say that these privileged people are speaking of how they would expect themselves to behave.

Let me share five reasons research shows why people often DO NOT leave abusive relationships. There are certainly more.

1. Society normalises unhealthy behaviour so people may not understand that their relationship is abusive.*

“Everyone collects data and exploits it for their own benefit.

Everyone learns about habit-forming techniques to attempt to influence people one way or another.

Everyone hides important information in the privacy policy.

Everyone ties me up in long-time subscriptions.

How could it possibly be bad – surely this is how business is done and I have to just learn to live with it.”

2. Victims feel personally responsible for the abusive behavior.

Self-blame is strong in all of us.

“I bought the wrong thing, but that’s probably just me.”, “I signed up for that trial period but it’s my fault I’m now stuck in a 12-month contract.”, “I can’t seem to stop checking notifications but that’s only my own lack of self-control.” “Theyused my Instagram photo about being raped but it’s my fault for not reading the terms of service.” “Wow I’m so bad at computers I’m sure everyone must be laughing at me behind my back.”

It is obviously never your own fault when you feel betrayed and are taken advantage of. But other people in our life seem to be coping so we often assume it must be.

3. If you stick it out, things might change.

You’ve had good times together, there is a possibility that things could get a lot better. There certainly are things you would miss. And now that the media is writing about ethics maybe these platforms will get it and start treating you better. I’m not sure how that will play with their business model, but you know, it can really only get better, can’t it?

4. You share a life together.

As part of many teachings around behavior and design, it is recommended that one lets the users invest time, effort and emotion in a service by having them for example upload pictures, change colors and profile pictures. Of course, the more a person invests in this “life together”, the less likely it is that they will want to abandon it, even when you treat them poorly.

5. Leaving is made difficult

I’m confident there are many of us who have experienced the ease with which we sign up for services, as well as the obstacles erected to prevent us from leaving.

Once we adopt a mindset where we allow profit to come at the expense of human well-being we are enforcing an abusive relationship.

If you as an employee want to do something to avoid causing harm to someone else, but your manager does not permit you, that is an abusive relationship. And to build on that, if you use design to coerce people to do things that are not in their best interest, that is an abusive relationship.

And should things fall apart, now you can blame your manager and your manager can blame his profit-based performance indicators.

When I finally acknowledged how the digital design industry was moving in the direction of conversion optimisation at any cost, and unethical behavioural nudging for profit maximisation, I was concerned many of us had completely lost touch with why we became designers.

Every student, coaching client and colleague I talk with share the same core.

“I want to help people.”

What also happens when you put yourself in a position to help people of course, is that you gain the ability to misuse that power, the ability to abuse. We need to recognise and talk about this power. Constantly.

Because if we don’t give it a voice, the abuse becomes invisible.

As it happens, having the power to help, and to influence others, is a slippery slope. You make compromises, You take one step in the wrong direction – a little nudge, a shove and sprinkle of dark patterns, some neglect of vulnerable people. Now the next step doesn’t seem that bad. And your actions did, after all, turn out to be profitable. You got a pat on the back from the people close to you. And the users, way across somewhere else, did after all choose to click all on their own.

Pretty soon you are the person saying…

Well hey, if they don’t like it, they can just leave.

Seeing the harm becomes ever more difficult as the harm itself just becomes part of a systemic habit loop and normalised. That’s why it becomes so important to make the harm visible, to create awareness.

A lot of harm is of course becoming visible today as we talk more about tech addiction, mass surveillance and data exploitation. Less visible is the part we, as designers, are playing in a race that can both empower and dehumanise at the same time.

A person recognised across the world as a a prominent design leader was last year asked on stage at a big industry event how the Hippocratic Oath should be applied within the field of design. The Hippocratic Oath, of course, is an oath of ethics historically taken by physicians and one of the most known Greek medical texts, of which a primary tenet has become: “First, do no harm.”

In a disturbing response, this design leader argued that doing no harm as designers would imply that we never do anything new and never take risks. Instead he argued that “We need systems in place to ensure that we don’t do too much harm. Or we don’t harm intentionally.”

Let me repeat those words:

“Don’t do too much harm…”

It is extremely dangerous when design leaders suggest that an ethical code would somehow be detrimental to the design outcome. Many designers are out there are listening, essentially hearing that risk-taking takes precedence over avoiding harm. That some abuse will be “worth it”.

Let me be abundantly clear.

- Ethical codes support risk-taking, that is what saves lives.

- Ethical codes support innovation and making new things. This is how medicine and life-supporting devices are made.

- Ethical codes support moving forward, just always aligned with the mindset of minimising harm.

That is why the ethical codes matter.

I will be honest, medical ethics, like any ethics, is not black and white. And medical history certainly has it’s share of disturbing abuse of human beings in the name of science.

But the availability of codes such as the Hippocratic Oath, The Declaration of Helsinki and The Nuremberg Code allows us to keep the conversation going. Because the codes themselves are not the final product but rather the topics that always need to be within our conversations to help us stay away from becoming the abusers.

As designers our curiosity should be driving us to explore the extensive and thoughtful work that has gone into reasonings around avoiding harm to humans. We should be reading all of it, because then we can begin to understand why something that may sound counter-intuitive is expressed out of care for human well-being.

Here are 6 things medical ethics can teach us:

1. It is not recommended to always treat patients as you yourself would like to be treated.

I’ve seen many designs that work well and efficiently for tech-savvy people. But not for the rest of the population. In Sweden, I know people who find it extremely difficult to pay for parking or public transport. Things that only a few years ago were second-nature to them. We treat people differently because we are all different, with different experiences, preconceptions and abilities.

2. Risk-taking to improve well-being is fine, but only with the full, informed consent of the person at risk.

This is the simple difference isn’t it? Instead of just taking my data, tell me what you are taking and why, how you will use it and how you will not use it. And what measures you are taking to protect it. In medicine there are ethical review boards that include people from different specialties and backgrounds. When in any doubt, ask help from a diverse review board to understand all the risks, and explain the risks to the people at risk.

3. People have a right to make decisions that are bad for themselves.

In a world of covert nudging where designers are working to influence people to do what they or their company has decided is best, we are working against the care you must take to allow for people to make different choices than the ones you believe are the right ones. Appreciate the importance of autonomy and give people the option of not following your lead.

4. Be open about lack of knowledge.

If you don’t know you don’t know. As designers we work with experiments and hypotheses. Expressing views with 100% certainty on “This is what users need”, “This is how they behave.” or “This is what they feel about the outcome” is irresponsible. Be open about your lack of knowledge to support necessary conversations about how we listen for mistakes in our assumptions.

5. Avoiding harm is not enough, you also have to take steps to contribute to well-being.

This is the difference between standing still and moving forward. If you’re not contributing to well-being, you may have to remind yourself why you become a designer.

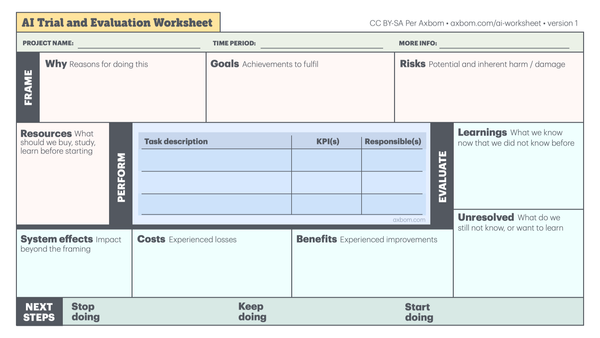

6. Think about, discuss and record ethical considerations and feel confident that you can justify your decisions.

In the end ethical design is a process, not a set of rules.

And by documenting your design decisions and your concerns along the way, you will feel immensely more confident and happy about the work you’re performing. We all make mistakes. Document them. Regularly. Do better next time. And make others aware.

Remember, it’s not the code of ethics that helps patients, it is medical personnel with a strong sense of understanding that they can potentially harm people.

It is not a code of ethics that helps users of digital services, it is design professionals with a strong sense of understanding that they can potentially harm people.

The code is there to support an ongoing conversation that contributes to that awareness.

Whereas medical workers often are close enough to touch and look into the eyes of their patients, in the digital space we are often many degrees away from the people we are influencing. In time, in space and even in the potential number of actors between our design and what the experience becomes.

This does not remove accountability, but instead adds a layer of responsibility. We, as designers, are the ones who can bridge that distance and help people in the now, become better aware of the people they are affecting in the later.

When I sit with developers and talk about the importance of accessibility I do not talk about technology. I do not delve into the many criteria of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines. I do not show them tools for validating their pages.

I talk about people.

I talk about Jenny who has a visual impairment and is trying to order a guitar. I talk about James trying to fill in a job application while his 2-year old is making a fuss in his lap. And I talk about Jasmine who struggles with her reading comprehension and has difficulties with metaphors.

I want to help developers understand why they are building for accessibility. If they understand why they will figure out the how. By being a designer who can trigger compassion, I build motivation to do the right thing. Equally important, I’m treating members of my team as human beings, not resources.

As a designer I can bridge the gap between the person who builds and the people being affected.

They may not be looking into each others eyes, or feeling each others presence. I may not always be able to get them to meet. But I want them to get as close as possible.

To support that conversation and awareness.

Last week I watched a news story on the ongoing pandemic in which a nurse explained how she walked into work every day with a smile and full of intent to help people. What she said had an impact on me: “The virus helped me remember why I chose this profession.”

I encourage you to work in ways that help you remember why you chose your profession.

Member discussion