In 1973, Ursula K. Le Guin wrote her award-winning story The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas. This short science fiction story describes an idyllic city, Omelas, where everyone is happy and healthy. The city celebrates its summer festival with flowers, delicious food, flute playing, and children racing on horseback. The bliss and pleasure embodied by the city feels too good to be true.

And it is.

The wellbeing of its citizens and their ability to flourish is based on a very specific phenomenon: the suffering of a child. In a basement room, this child is kept in darkness, terrified, and without human contact, year in and year out. The description of the child’s suffering is heartbreaking and morbid.

The child is no secret. Everyone in the city knows. It is explained to young residents between the ages of eight and twelve. And they know that their own happiness, loving relationships, and lavish environment depend on the child's misery.

Many, not all, take the time to visit and observe the child. Many are initially shocked but over the years learn to come to terms with the necessity of the arrangement – to protect their own and the city’s prosperity. But every now and then one of these observers walks away. Out through the city gates, never to return.

They walk away from Omelas.

This story is constantly with me as I figuratively see the “children in the basements” of the modern tech industry.

Children and pregnant girls working in mines to extract minerals. Young adults witnessing violence and abuse day after day in their roles as moderators and “AI” workers. People with disabilities facing digital stop signs. Disinformation and deceit that brings conflict and impoverishment. Violence facilitated by remote technology. Surveillance and biometric abuse that strip people of their self-determination.

As I continue to hear and read countless stories of abuse every week, my conviction and determination to continue writing and speaking out about human rights issues in the tech world only grows stronger.

The vulnerable people in the tech world are no secret. They are known but rarely mentioned. Every now and then, a journalist visits their “basement rooms” and reports on brutal distress, hardship, and injustice. For a moment, readers and viewers are upset when witnessing second-hand the naked truth of how people are exploited to enable the growth of the tech industry.

But the outrage is short-lived.

People soon come to terms with the fact that their happiness, relationships, and thriving environment require someone else’s misery. Behind the scenes, workers continue to contribute the natural resources and trauma necessary for the technology to work for its users. Or the technology itself harms through sheer negligence, obliviousness, or superiority.

Le Guin’s story feels cut off, leaving the reader shaken after the fifteen minutes it takes to read it. Who am I, really, in this story? It’s deeply uncomfortable. I just want to walk away from the horrific depiction—appreciating its brevity.

But the contrarian perspectives are flustering. There are people who stay and embrace their own wellbeing, building upon the rule that current circumstances rest on, finding it ever harder to judge what is unjust and what is dignified. And there are people who choose to leave, to walk away.

Who, then, remains to reform?

As long as I muster energy and am able to hold myself together, I want to continue to understand, pay attention to, and explain how technology is a force that profoundly affects equality, power structures, and universal wellbeing. What are current conditions – and what could they be when we do things differently. The multitude of diverse paths. Albeit a small contribution to a slow reform, it's where I see myself providing value.

Thank you dear reader, encourager and contributor, for being part of the journey.

Sketch of the month

Dialogue:

"Are you already in bed?"

"Yes."

"I thought someone was wrong on the internet."

"Lots. But it turns out I have more space for love when I don't fight. I'll write something educational tomorrow… Are you coming?"

Quote of the month

What makes LLMs work isn't deep neural networks or attention mechanisms or vector databases or anything like that.

What makes LLMs work is our tendency to see faces on toast.

– Jason Gorman

Source: mastodon.cloud

Next talk

On July 3rd I'm giving a talk in Manchester at the Camp Digital conference. And it's probably not a topic most people expect me to talk about. I'll be giving a closing keynote on the spectacular lies of maps. The day will take place at the prestigious Royal Northern College of Music and there are a few tickets left. Check out the full schedule.

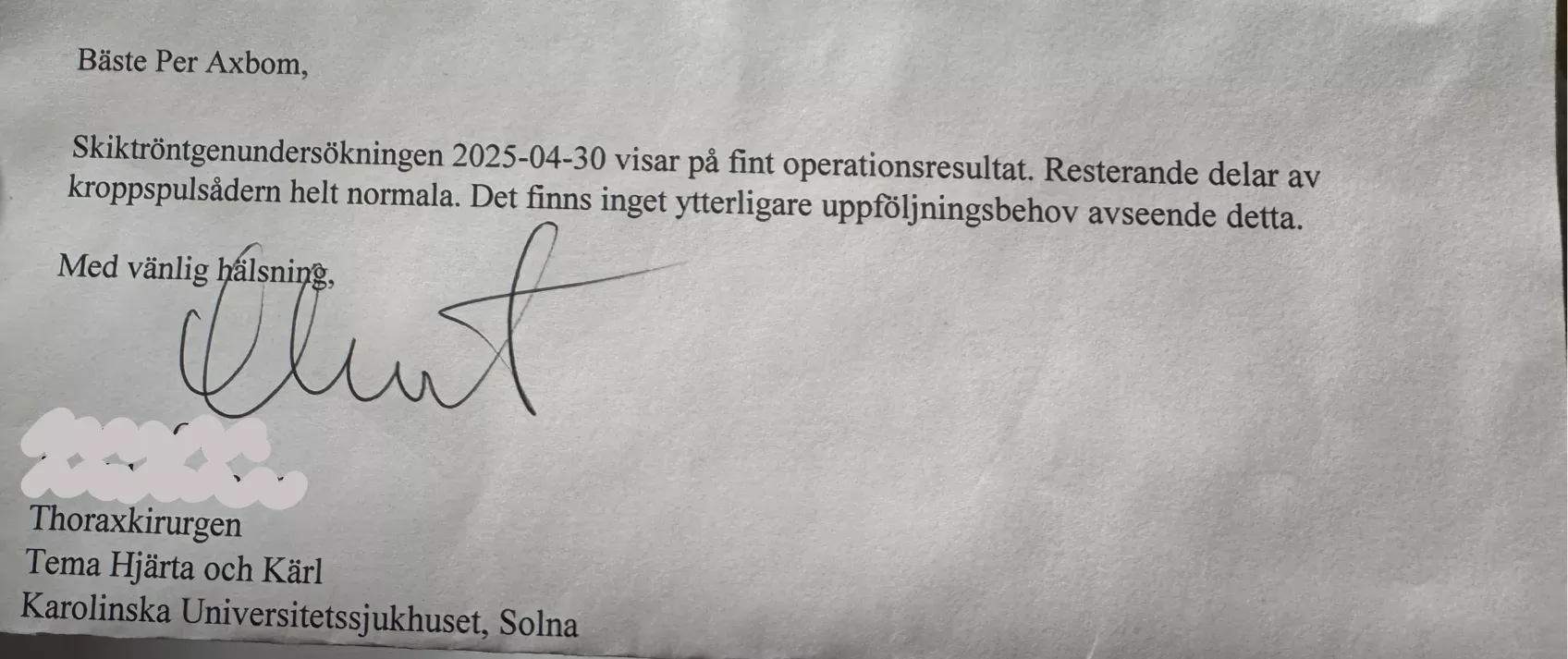

How's the heart?

I want to spend more time writing about my experiences over the past year, but this latest update is worth sharing:

"Dear Per Axbom, The CT scan on April 30, 2025 shows a good surgical result. The remaining parts of the the carotid artery are completely normal. There is no further follow-up needed in this regard."

– Thoracic surgeon.

It's now possible to support my work. As a Supporter, you contribute 5 Euro per month.

Trivia: Le Guin came up with the name "Omelas" after she saw a road sign in her rearview mirror that read "Salem, O." (Oregon).

Member discussion