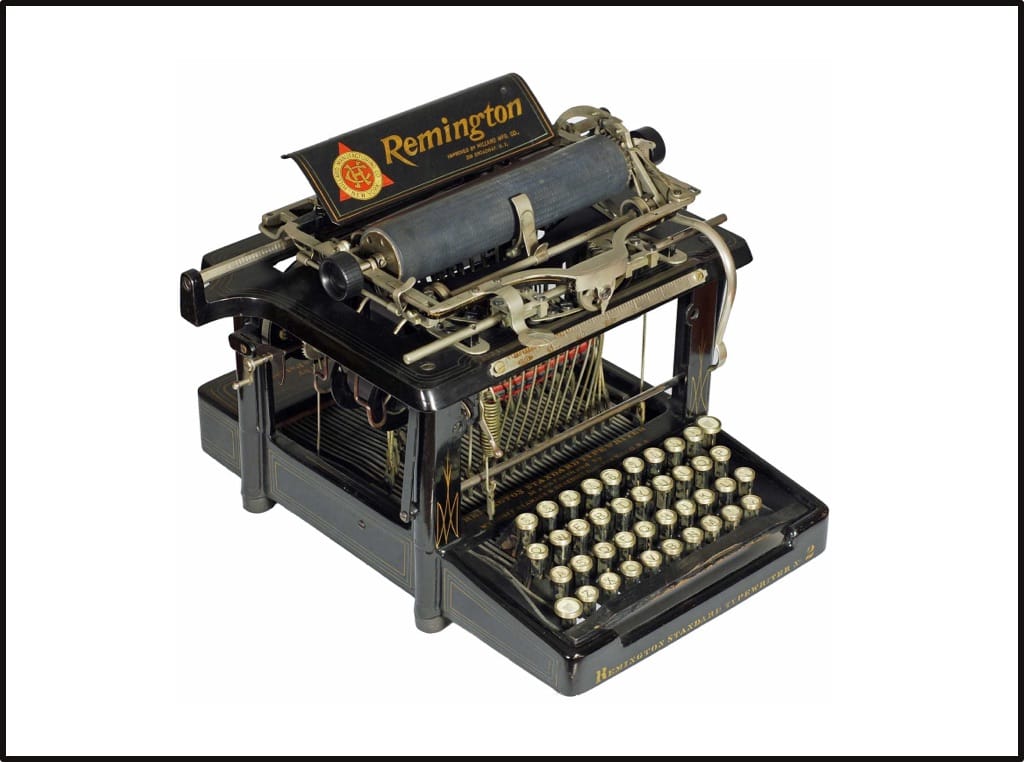

Pictured in the featured image is my Remington Standard 12 typewriter from circa 1925, with a Swedish keyboard. Remington is notable as a brand of typewriter because their first two typewriters introduced features that are still in use today on computer keyboards across the world.

Now, get back to reading about typewriters!

Feature 1: Qwerty

The Qwerty keyboard layout was invented by Christopher Latham Sholes in 1868 and adopted by the first Remington typewriter in 1873.

Many people believe that the Qwerty keyboard layout deliberately placed keys to slow down typists, so that the typebars (the moving bars holding the hammers with the letters) wouldn't get jammed. But that's only partly right.

What Sholes did was place letters that were frequently used together far apart from each other in the mechanical circle that held the typebars. So for example the common letter pair "TH" meant that the respective typebars for T and H had to be hung far apart. This enabled typists to type faster, not slower, because it was now less likely for the typebars to get jammed. It wasn't perfect, but better.

Typing faster without typebars getting caught on each other was made easier when certain letter keys were moved further apart from each other.

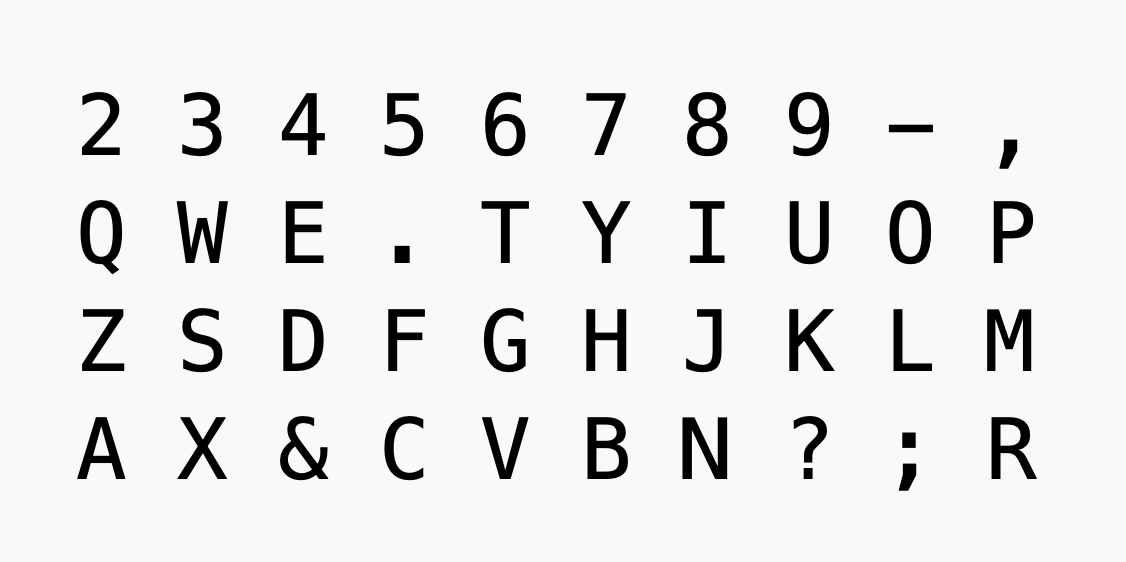

What you also may not know is that the original patent by Sholes for the Qwerty keyboard layout had the keys placed like this:

To save on manufacturing costs, the digits 1 and 0 were simply not represented, and typists would just learn to use capital 'I' or capital 'O' to represent those numbers. Punctuation marks were also interspersed among the alphabetical letters, most notably with the period situated where we today find the letter "R". The "R", funnily enough, is on the bottom right, where we now find the period.

It was only in 1873 when E. Remington and Sons bought the patent and manufacturing rights for the Sholes & Glidden 'Type-Writer' that they modified the keys to something that is more similar to what we are accustomed to today. And yes, in case you were wondering, that's the same Remington that made firearms.

Interestingly, moving the R to where it is today enabled the typing of the word "typewriter" using only one row of letters.

While there have been attempts to design the ultimate keyboard layout (such as the Dvorak Simplified Keyboard layout claiming much improved ergonomics) it has been found repeatedly that one layout over another does not make a significant difference. Good typists learn to type fast whatever the layout. No need to fix something that isn't broken, and we've now had the Qwerty layout for more than 150 years.

A fair number of business books mention the Dvorak keyboard as superior and Qwerty as inferior, and while those stories live on, they have largely been debunked. Long story short: the studies claiming Dvorak was faster to type with have been found to be flawed in their execution or in their selection of sample populations.

When it comes to ergonomics and the placement of keys according to how often certain letters are used, this is shaky when considering that the letter placements are simply copied to other countries and languages, or may differ among professions (think programmers versus lawyers). Any such benefit also primarily affects people who touch-type, which many studies reveal to be only about 20% of computer users.

That being said, there are of course many enthusiasts who love to experiment with different layouts. Digital environments truly enable completely personalised key placements, which can help reduce finger strain if you are willing to re-learn typing. I myself am a bit intrigued by the Workman layout.

Feature 2: Shift key

The Remington no. 2 was released in 1880. One of its most notable proponents and users was mystery writer Agatha Christie. This model introduced the first Shift key. Because of its popularity, this of course is also the typewriter model that truly helped the Qwerty layout become mainstream.

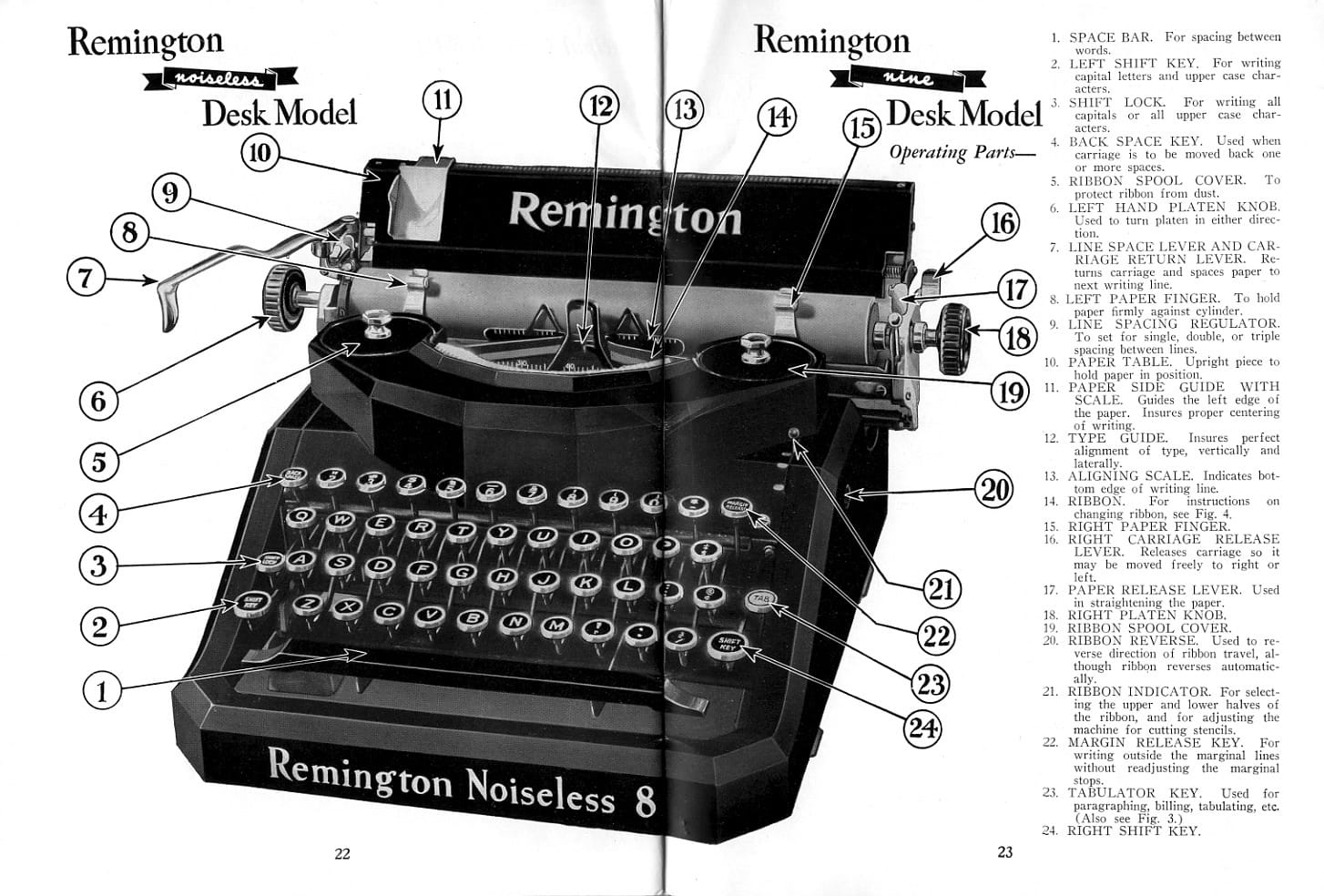

Previous typewriters only had capital letters and the Remington no.2 made it possible to type in both upper and lower case. It was called a shift key because it mechanically shifted the entire carriage upwards so the other character or letter on each typebar would strike the ribbon and paper.

There is no mechanical shifting of letter placement taking place in today's keyboards of course, but the name lives on, as do many more keyboard related terms based in mechanical functions.

The legacy of the carriage return

Some of the first computers I used had a key called carriage return (often today referred to as "Enter", or sometimes even "Return"), even though they of course had no physical carriage to return to its original position. The carriage return key placed the cursor at the beginning of the next line on screen.

Both CR (carriage return) and LF (line feed) live on as terminology in computer programming. In typewriter lingo a carriage return moved the whole carriage to the right, to enable typing at the leftmost position (but on the same line), and a line feed moved the the paper up while the carriage stayed at same horizontal position.

So what we are used to, pressing enter to move the cursor to the beginning of the next line, would formally be a CR + LF, i.e. a carriage return plus a line feed. Which, to be fair, is how many carriage return solutions were implemented.

In computing, both CR and LF are ASCII control characters, so when sending a command to a printer to cause a line break that starts at the leftmost position, this would be coded as CR (codepoint 13) + LF (codepoint 10). This practice has continued on for screen-based interfaces where non-linux based systems (such as Windows) use the combination "\r\n" to denote a return to the beginning of the line combined with a new line.

In some operating systems (notably on Apple Macintosh, but also Linux) the pairing of these two codes was abandoned in favor of a single command "\r" (Mac OS 9 and earlier) or "\n" (Mac OS 10 and later) to accomplish the same thing. This difference between operating systems has often been a source of frustration for engineers.

Demo of a person using a manual carriage return that also creates a line feed on a 1969 Hermes 3000 Vintage Typewriter. Source (Youtube)

Backspace did not delete

The backspace key on my typewriter (in Swedish: "bakslagstangent") of course does not delete the previously typed character but it moves the carriage into a position where the previous character can be 'overtyped'. Hence backspace is the exact opposite of space (move the carriage one space back rather than one space forward). This function could also be used to create combinations of characters. Some early typewriters did not have an exclamation mark so one would use the combination of "apostrophe backspace period" to give the appearance of one.

Later on of course came the correction tape that allowed the application of a thin strip of white tape over misstyped letters, thus making it possible to type a new letter in the same place.

Backspace on computer keyboards, as you know, just immediately deletes the preceding character.

Machines of compassion

The first mechanical typing machine was invented by italian Pellegrino Turri for his blind friend Countess Carolina Fantoni da Fivizzano so she could write him letters. It's suggested they were love letters.

In one of my favorite blog posts, The Technology of Compassion, Norman R. Ball retells the story of Pellegrino and Countess Carolina, and delves into how much mechanical typing machines have meant for people who are blind.

The more you know about them, it's hard not to love typewriters.

Writing "The End." on a typewriter.

Sources

Member discussion