It's not always obvious how the idea of ethics should merge with the very broad concept of digital technology. Especially when the word ethics brings to mind a whole field of academia rooted in ideas brought forth by greek philosophers. This is my contribution to framing digital ethics in a way that makes it more useful for everyday work with digital products and services.

Three branches of ethics

Let's start off with the different branches of ethics that are central to conversation, and generally studied by philosophers. I'm not talking about moral theory yet (utilitarianism, etceteras) but rather about different perspectives when approaching ethics as a concept:

- Normative Ethics

- Meta-ethics

- Applied Ethics

Normative ethics

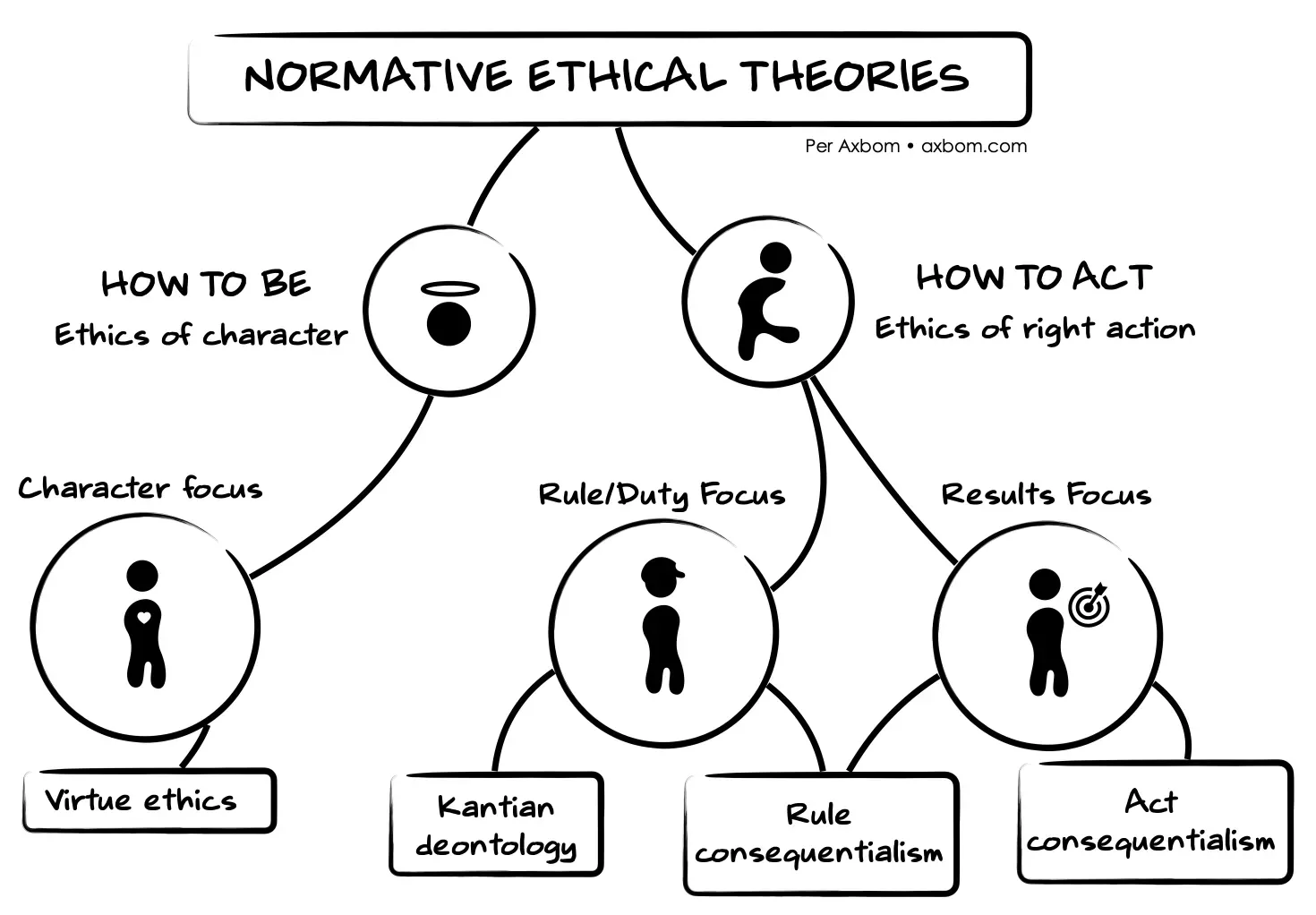

Normative ethics seeks to answer how people should act in a moral sense. It's concerned with questions like "how should I be" and "how should I act". It rests on the idea that moral principles need justification and explanation. There are of course many moral theories but these are the big three categories.

- Virtue ethics posits that an act is morally right because it is one that a virtuous person, acting in character, would do in that situation. This requires that we define the traits of a virtuous person, often associated with human nature: for example rationality, curiosity, empathy and cooperation.

- Deontology rests on the premise that the morality of an action should be judged on whether that action itself is right or wrong under a series of rules, rather than based on the consequences of the action. Put simply: if the outcome of an action is harmful, the action can still be considered moral if it was performed according to a predefined set of morally approved behaviors. i.e. "Something bad happened but I still did the right thing."

- Consequentialism is a class of moral theories that treat the consequences of actions as the ultimate basis for judging whether an action is right or wrong. The most well-known of many consequentialist theories is utilitarianism, and specifically hedonistic utilitarianism. This theory says that aggregate happiness is what matters, i.e. the happiness of everyone, and not the happiness of any particular person.

Character-focused theories start with the question "How should I be?" and the answer determines "What should I do?". Action-focused theories start with the question "What should I do" and the answer determines "How should I be?".

In my mind the power of virtue ethics lies in its attention to long-term thinking, adopted behavior, habits and consistency. One doesn't only want to do good, but also be good. By practicing a way of being one increases the likelihood of morally good outcomes.

Conversely, the power of consequentialist ethics lies in the ability to assume responsibility for outcomes that were not intended, and use that insight to adjust and change future behavior.

When it comes to topics like human rights, many philosophers argue that deontology (rules) and consequentialism (results) overlap. While often associated with deontology, the rules of human rights can only be justified when referencing the consequences of having those rights. When the same behavior is prescribed by both deontology and consequentialism this is often referred to as Rule Consequentialism.

So, even though these areas of ethics appear to be distinct they are also very much interrelated.

Meta-ethics

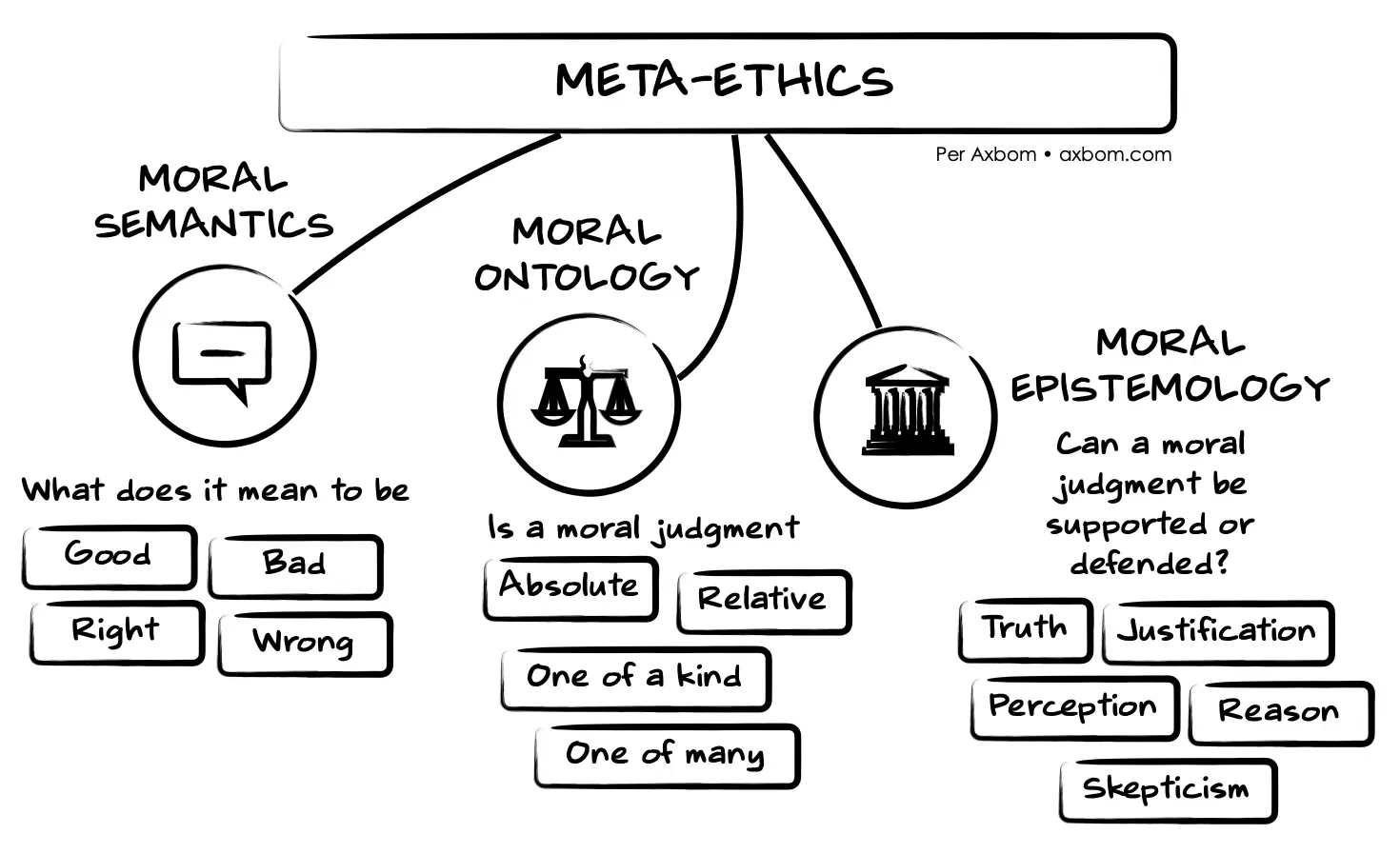

The study of meta-ethics looks at what moral judgment even is. What is goodness and how can we even tell what is good from what is bad. You may express it as trying to understand the assumptions that are part of normative ethics.

Meta-ethics has been broken down by Richard Garner and Bernard Rosen into three distinct areas:

- Moral semantics looks at the moral terms and judgments we use in moral philosophy and try to determine their meaning, if those meanings can be seen as robust and true and if they are relative or universal.

- Moral ontology looks at moral theories and judgments, trying to understand if they are absolute ("thou shalt not kill") or relative ("unless someone tries to kill you") and if moral principles differ between people or societies.

- Moral epistemology strives to understand if moral judgments can be verified by determining how beliefs and knowledge are related, including what it means to say that we "know" something.

Noteworthy is that philosophers working with meta-ethics are not really concerned with whether or not a person or an act is ethical, they are concerned about the field of ethics itself, and what substance it has.

Applied ethics

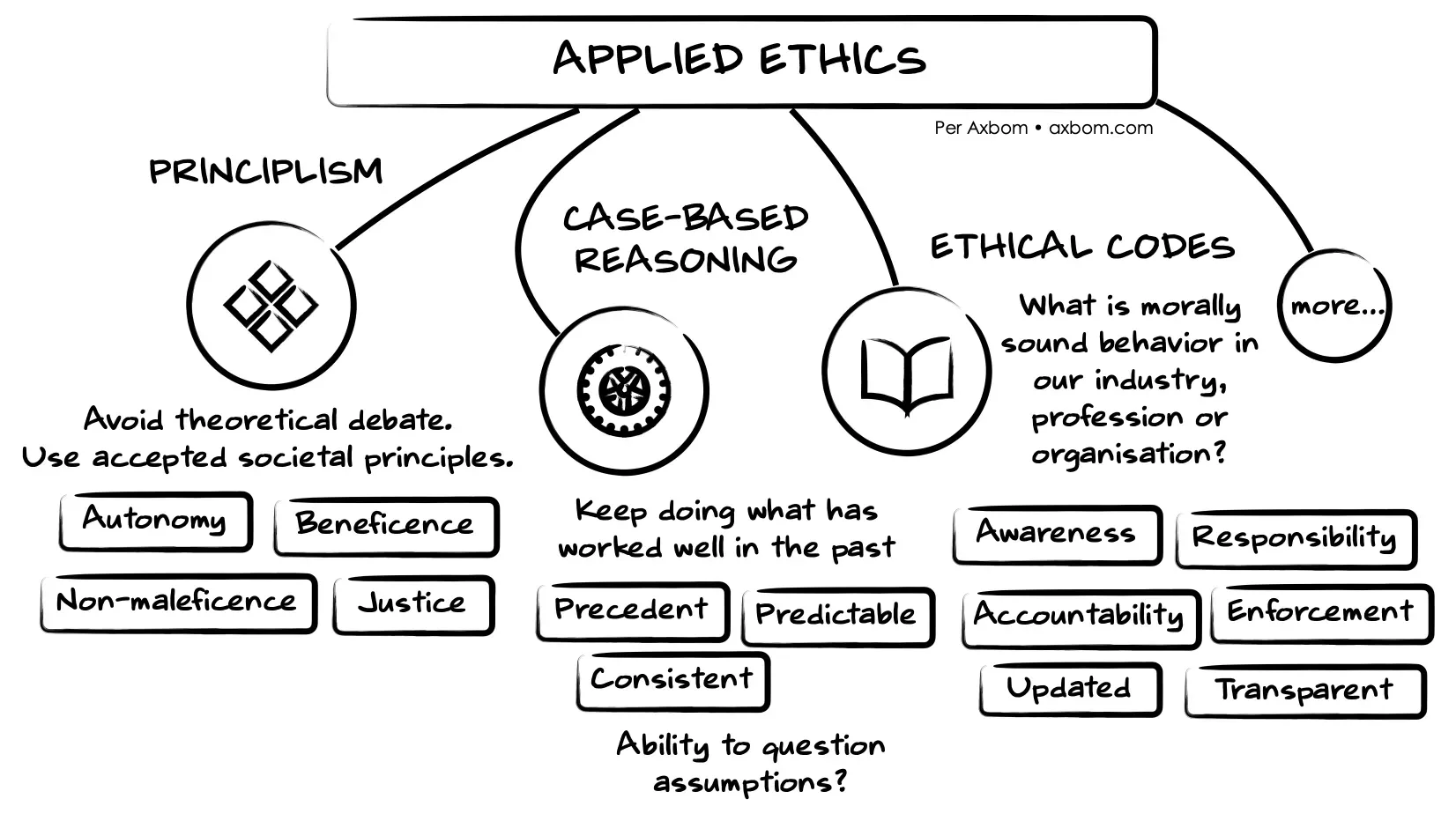

In the third and final main branch of ethics I'm referencing in this article, it's now time to act. Regardless of moral theory, humans perform acts all the time without running them through a process of determining what theory within normative ethics may be applicable.

But sooner or later professionals in most industries run into the insight that their everyday work has effects on other humans, on society and on universal wellbeing. Effects that can be very tangible and momentous. They come to the realisation that more reflection and consideration is needed to evaluate the outcomes they contribute to, and effort is required to avoid and mitigate the unwanted effects.

Applied ethics is the practical application of moral considerations to help people make decisions with more thoughtfulness. It is concerned with finding the correct approach to moral issues in both private and public life, often exemplified by professions in health, technology, law, and leadership.

Applied ethics grew as a field out of the debate surrounding rapid medical and technological advances in the 1970s and is generally seen as an important branch of moral philosophy.

The rise of digital ethics

Digital ethics is growing out of the rapid advances in digital technology and internet-based devices and services. As the more sinister effects of digital technology are becoming apparent, the call for ethics in digital development is permeating throughout society.

And while it may often be defined as a subset of ethics, applied ethics is necessarily multi-disciplinary as it requires specialist understanding of potential ethical issues. Within information technology this could be exemplified by expertise surrounding privacy, machine learning or data networking. Due to the ubiquitous nature of digital, however, the expertise required for various considerations could just as well pertain to copyright law, domestic abuse or biometrics.

Seeing the potential for harm

Most digital products are developed not with the multi-disciplinary expertise required for ethical consideration, but with the expertise required to build something (often as quickly as possible) and get it shipped. Common drivers for building and investing in digital products and services are financial growth and improved efficiency for a defined subset of people.

This is one reason the consequences of digital development often becomes apparent relatively late, not uncommonly years after a digital product is released into the world. Another reason is of course the very novel nature of interconnected digital systems: there is still much to be understood and researched. Some systems that were not designed for the internet also become something else when integrated into a universal network.

It's also important to remember that there are often many voices with early warnings about the consequences of technology. Voices that are systematically ignored, silenced or disempowered. Voices all-too familiar with harm and with an inherent ability to recognise it.

Seeing and recognising the potential for harm is an essential factor in course-correcting the manner in which digital development occurs. In understanding how to be and how to act. The examples of harm we come across today are all examples to learn from when choosing the path ahead and merging applied ethics with digital development.

Choosing moral theory

Working on a team with other people in a busy environment with tight budgets and timelines doesn't present itself as the optimum foundation for reflective reasoning and considered compassion. Especially if there is a lack of awareness, expertise or mandate for managing ethical challenges.

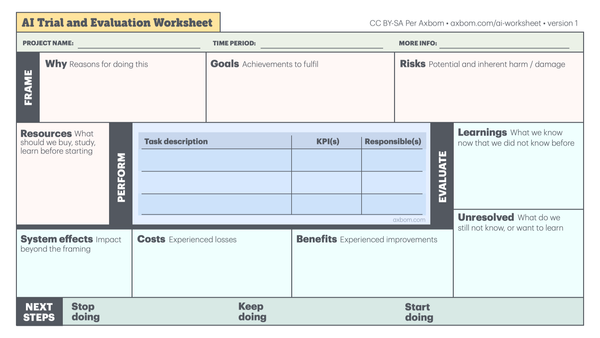

While normative ethics consciously or unconsciously will underpin any reasoning about how to act, digital ethics is not about arriving at an agreed moral theory and using that as an overall guide for digital development. Instead, applied ethics is about making time for ethical reasoning and making this a part of ongoing work and workflows.

It will become evident that most applied ethics will naturally fall into some form of consequentialist thinking, looking at the outcomes and impact of building and introducting something new. But I don't believe that this should exclude the possibility of adopting variants of virtue ethics also in the workplace. Discussions about who we want to be can be a huge contributor to the way a team works, makes decisions and manages maleficent outcomes.

Examples of applied ethics approaches

This is no exhaustive list of the ways that workplaces approach applied ethics, but I hope to provide an understanding of how moral reasoning is often simplified (with good reason) to help more people without an understanding of normative ethics get into the mindset of moral decision-making.

More often than not, a mature organisation will be pulling from many different ways of managing ethical outcomes to ensure positive outcomes. This is similiar to how product organisations rely on both quantitative and qualitative research data to verify assumptions and guide ongoing work.

Principlism

A very popular form of applied ethics, principlism is designed to avoid debate at the level of normative ethics. If offers a practical approach to dealing with ethical dilemmas in the here and now of everyday work. You could consider it a form of rule consequentialism.

The four principles of principlism are:

- Respect for autonomy. We allow an individual to be self-determining and to make decisions for themselves without undue pressure, coercion or other forms of persuasion.

- Beneficence. We have an obligation to act for the benefit of others.

- Non-maleficence. We refrain from causing deliberate harm or intentionally avoid actions that might be expected to cause harm.

- Justice. We do what we can to ensure that costs and benefits are fairly distributed.

While they may feel self-explanatory, I like to emphasise that the principle to keep an eye on here is justice. This is because it is possible to act with both beneficence and non-maleficence and still not be within your moral rights. It may be that we can create major benefits for some, while the interests of others are overlooked. The principle of beneficence could be declared to allow moving forward with a helpful solution, but when evaluating the decision based on justice it may fail the criteria of fairly distributed costs and benefits.

A principlistic framework doesn't require the analysis and justification so prevalent in normative and meta-ethics. Instead it's enough that there is a broad individual and societal agreement about the importance of prescribed values. Principlism remains a dominant approach to ethical analysis in healthcare.

Case-based reasoning (CBR)

If you have had a problem with your computer that you manage to solve, and then later help a friend with their computer that is exhibiting similar symtoms, you are using case-based reasoning. The idea of a legal precedent is also an example of case-based reasoning. Case-law rests on the idea that forming rules based on previous outcomes will help us reach similar and predictable outcomes today and in the future.

For purposes of using computers for case-based reasoning, the process has been split into four steps:

- Retrieve. From memory (or archives), find the closest likeness to what you are trying to learn or achieve, preferably with a successful outcome.

- Reuse. Apply the information from memory to the current situation.

- Revise. Test the new concept or solution to gauge its performance with your expectations. You may need to revise and test again.

- Retain. Add this to memory for later retrieval. This is now a new case to be retrieved in the future.

The strength of case-based reasoning is that output becomes consistent and predictable. Once a successful outcome has been produced (from a moral perspective) it is more likely that we will achieve the same moral success by applying similar rules.

The glaring weakness of case-based reasoning is of course the assumption that if something was true in the past, it should be necessarily be true now and in the future. The risk is that too little attention is paid to changing variables in the environment. What we deemed as successful in the past may not be the definition of success today, and the revisions we apply can lead to unpredictable results in the real world.

This is where the reasoning comes in. While seeing the same symptoms, the underlying problem may not be the same. Instead of fixing your friend's computer, you may make the problem worse.

A critical part of case-based reasoning is therefore to understand whether the current situation truly is similar to a previous one that comes to mind.

When talking about case-based reasoning I tend to think about the TV-series House. In the show Dr. Gregory House consistently disagrees with the diagnostics of his fellow physicians. He bases his disagreement on small and subtle hints and insights about the ill patients. Often what looks the same is not the same, and this mindset is a valuable one to strive for.

Manifestos and Codes of ethics

As a professional coach I ascribe to the ICF Code of Ethics. This is a way of codifying what is deemed as good and bad behavior. Through my education I have role-played and had extensive conversations about different scenarios to become more aware of ethical dilemmas and how I am expected to act in coaching situations where moral decision-making is needed.

A code of ethics tied to a professional organisation means that moral responsibility becomes apparent and transparent for people who hire the services of a professional tied to that organisation. It can be used to hold professionals accountable and pushed to their limit can lead to the exclusion of individuals from an organisation.

While we have yet to see this type of enforcement for designers, developers, engineers and product owners in the digital space, there has certainly been a large uptick in the number of manifestos authored by and for digital makers in recent years.

At first these manifestos may appear powerless in bringing about real change in the industry, but I believe for many they are an important first step. They encourage the important conversations about one's own role in good and bad outcomes, and invite people to assert their own standpoint on different issues. It's an entrypoint for those not well-versed in ethical consideration.

A well-written, well-researched and inclusive code of ethics can help an organisation surface and pinpoint key areas with moral implications, and often create an awareness of responsibility that was not there before.

Moving forward I am hoping to see more organisations (both workplaces and industry hubs) formally put in place guides, codes and manifestos that are more strictly tied to accountability for the professionals associated with these organisations.

A clear benefit of these codes lies in defining behavior and situations that are malum in se, inherently wrong regardless of any regulation. This goes beyond malum prohibitum, actions that are wrong because they are prohibited. For the digital space, which often moves faster than regulation can keep up, I would argue that consistently outlining inherent wrongs is quickly becoming an imperative for ethical decision-making.

Where to go from here

In my work on digital ethics there is a balance between prescribing what the right thing to do is, and what the right thing to bring up for consideration is. While I of course have my thoughts on malum in se, my efforts as a teacher are not intended to impose rules about right and wrong. I want to inspire and encourage reflective thinking about what individuals and teams want to accomplish related to "being good" and which of their own actions may have an adverse impact on that goal.

What I have come to realise is that an understanding of the importance of digital ethics increases with the number of examples of ethical dilemmas that can be provided. This also boosts a willingness to engage in conversation about doing the right thing.

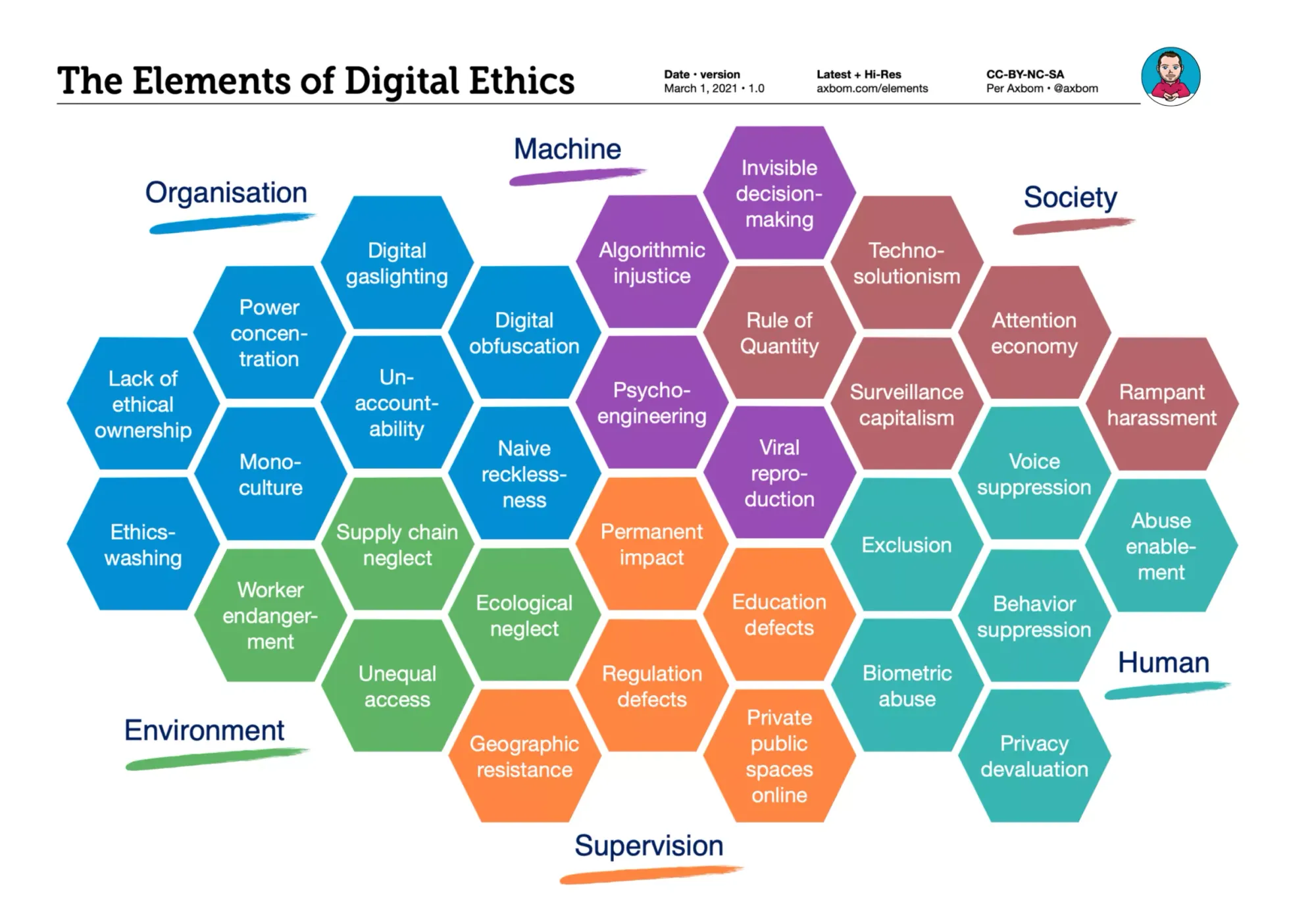

One tool I have produced with an agenda for teaching is The Elements of Digital Ethics. This is a chart that provides a summary of 32 different elements, or topic areas, that hold potential for negative impact in digital design and development.

When I introduce this diagram, two common critiques can be:

- the elements are framed in the negative rather than the positive outcome

- there is a lack of stated aspiration, as the elements won't themselves tell you why or why not there is a notion of good or bad tied to each topic area

My answer addresses both points. All the elements in the chart will not apply to all ethical issues in the digital space. Their purpose is to identify digital industry areas where moral dilemmas have commonly been surfaced. The negative expression of the topics in the elements are examples of real concerns raised by media, subject matter experts and digital creators themselves.

As such, I am tying the elements to real-world situations, the intent being to make them as practically useful as possible.

The Elements of Digital Ethics is not a manifesto or guide on how to act. It's an artefact to encourage conversation. It does not tell you what to do, but instead helps you more clearly see topics that you may want to consider for ethical evaluation.

What method, theory or framework you use for this ethical evaluation is not for me to dictate. In the end I would argue that The Elements of Digital Ethics do their job, which is to assist reflective reasoning when there is often a lack of awareness and understanding of where to begin.

An added bonus for companies that do engage with the topics covered by these elements is that their documented reasoning will help as reference when certain actions are questioned by outside parties. The ability to be transparent about ethical reasoning creates trust and mitigates concerns that can easily grow out of control.

Is digital ethics too broad?

A question that sometimes arises is if digital ethics itself is too broad of a subject to deserve its own umbrella term within applied ethics. Indeed, there are many related sub-topics that already are being worked on by researchers, such as AI ethics, privacy and deceptive design. Some of these are exemplified by one or more elements in the chart.

We need to remember that ethics itself is about human behavior: how to be and how to act. This is very broad by nature. If anything, reflecting on moral responsibilities of the digital industry serves to focus attention to the many ways in which the specific traits of digital (networking, speed, distance to subjects, encoded obscurity and more) can make it harder or easier to understand how we should be and how we should act.

And this is what the elements provide, a framework for understanding the multi-faceted industry and where there is potential for moral dilemma. One person or team may not be able to address all these issues, but can decide if they should be addressed, what further questions this raises, and who can help them in that work.

Digital ethics is broad, but also specific, because online services rely on many similar traits when it comes to storage of information, exchange of information, growth, accessibility, user management, and hardware dependencies – to name a few.

When we work with digital products and services, their inherent complexity should not be a hindrance, or excuse, for ignoring moral responsibility. But we also need to acknowledge that in a professional setting we need a structured approach that aligns with ongoing operations without disrupting the business. Something that would likely kill any initiatives to engage in deeper moral consideration.

This is why I'm looking forward to seeing more organisations and teams design and integrate tools and workflows for ethical reasoning in ways that make sense to them. And start sharing them with the world.

Do let me know what your next step is.

Member discussion