At the Adobe 99U conference there was an on-stage conversation between author Courtney E. Martin and Tim Brown, CEO of design firm IDEO. During the interview they touched upon the topic of ethics. Author and design consultant Kim Goodwin reacted to the exchange, calling out Brown’s remarks as “a disturbing statement”. I agree, and I couldn’t let it go. We need much more clarity about design ethics from design leaders, and I want to break down how Brown’s statements are misleading.

Note: This post also led to the development of the talk I first presented at UX Copenhagen 2020.

The problems start around the 23:40 mark in the recorded video where Martin tells Brown she wants to “talk about ethics a little bit because I know you’ve been deeply involved in thinking about the ethical life of designers and the ethical mandate for design as a whole”. She starts him off by alluding to the Hippocratic Oath, an oath of ethics historically taken by physicians and one of the most known Greek medical texts.

Martin to Brown:

You’ve been working with a lot of other designers thinking about what is our ethical mandate, what is our Hippocratic Oath for design. Can you talk about how you’re thinking about that these days?

Brown’s response:

Yeah, well one thing it’s definitely not, which is it’s not the Hippocratic Oath as we think about it in the medical world, because I think if we made the oath to first do no harm as designers, we would likely never do anything new. I think that would be unfortunate. I think we need systems to ensure that we don’t do too much harm, or we don’t harm intentionally. But I worry about an automatic reaction to the kind of ethical dilemmas that we have today, with technology, to be, we’re not gonna take any risks. I would rather see us make the oath to being extremely adept learners, and not disengage.

Instead of answering the question, Brown goes into defensive mode, arguing that taking risks is part of design and how he fears that the current “automatic reactions” to ethical dilemmas will remove risk-taking from design.

I want to address the distressing dissonance in those remarks.

Hearing and reading Brown’s response, he seems to make some curious assumptions:

- Brown argues that an adherence to the Hippocratic Oath would mean that there is no innovation. I would argue the opposite. The original oath was written between the fifth and third centuries BC (most modern scholars do not attribute it to Hippocrates himself). Medicine has seen a fair bit of innovation in the thousands of years since then. To be fair, though, it has been modified numerous times and if used in professional settings it is often the 1964 version by Louis Lasagna that is used. More importantly, it is always supplemented or substituted with regularly updated ethical codes.

- Brown argues that being ethical in accordance with the Hippocratic Oath means taking no risks. Again, it’s quite the opposite and the oath actually encourages risk-taking. Why? Because risk-taking saves lives. Primum non nocere (first do no harm) is a tenet of several versions of the oath, but there is no intervention in medical practice that does not also have risk. Thus one can not avoid risky treatments. Not doing anything can be as unethical as doing wrong. It’s about involving the patient and having their informed consent. It’s not inaction.

- Brown seems to imply that doing nothing is what creates the least harm. But in truth, we need innovation and new designs to reduce and mitigate the widespread systemic harm that is a daily reality for many people. To heal, we need invention and accessible distribution of curative interventions.

Ironically, the thousands of year old oath appears to actually promote much of what Tim Brown has in mind when he himself reflects on the road ahead.

The fact that ethical guidelines encourage risk-taking may seem counter-intuitive to a layperson of ethics. Given the amount of time Brown is said to have spent thinking about ethical mandates with his peers, I would have hoped for a more considered response.

Why the Hippocratic Oath matters

Courtney Martin’s original question was framed around “what is our Hippocratic Oath for design?”. It’s an open-ended question. Here are a few things I believe the design community can learn from medical ethics. Some I bring up because they address common myths. I’ll dissect the variants of the oath and more additional principles in a future post.

- Use the Hippocratic Oath to serve as a reminder of who our profession serves. The phrase “First, do no harm”, although not even part of the original oath, is about the concept of serving people first. It acknowledges that we have power to harm people. In medicine this power of authority is today obvious; in digital design, many are just waking up to it. The principle stresses avoidance of intentional harm.

- Risk-taking to improve well-being is fine, but only with the full, informed consent of the person at risk. This same premise is for example why we have regulations around information to people trading in financial instruments. Make sure that you gather a comprehensive amount of information to assess, and communicate, risks and benefits. This is why research matters.

- It is not viable to always treat patients as you yourself would like to be treated. That would assume you know them to an extent that they can only know themselves. Never assume you know what individuals need or want.

- People have a right to make decisions that are bad for themselves. People may have lifestyles you do not agree with, or even choose not to accept treatment that could save their life. Other people’s habits and values are allowed to differ from your own. You can inform them but you can not coerce them.

- Be open about lack of knowledge. Never be afraid to tell people when you need their help in managing an ethical dilemma. But also, be transparent about unexplored potentials of negative impact. Allow others to point out weaknesses in your product or design.

- Avoiding harm is not enough, you also have to take steps to contribute to well-being. This is what design should be all about.

- Think about, discuss and record ethical considerations and feel confident that you can justify your decisions. In the end ethical design is a process, not a set of rules.

But can we create without generating harm?

During the Twitter conversation following Kim Goodwin’s reaction to Brown’s comment, another point was brought up. Designer Joe Lanman asked, rhetorically:

In a complex capitalist society don’t most things cause some harm somewhere? Pollution, exploitation, etc?

I think this is a valid point and a reason even people like Tim Brown may struggle to find solid ground for an ethical frameset. It’s hard to make things without someone being hurt. But the challenge of this should be an incentive to designers, not a deterrent. It is hard – let’s figure out how we can make it easier.

I can support the notion that the creation of anything – no matter how benevolent it seems – will inevitably exclude or affect a select group of people in a negative way. In fact, Sarah Mei has a lengthy thread on Twitter going deep into the impossibility of a purely positive effect. But I don’t want to support the notion that “First, do no evil” therefore is a useless tenet, or even a limiting one.

While all medicines have side-effects most of these are known, through rigorous research and testing procedures, and communicated. Hence they can affect your body in negative ways while also contributing to a healing process. Prescribing the medicine is an act of agreement between physician and patient, where an informed consent (side-effects communicated and understood) must take place.

The act of “First, do no evil” within the space of design, would for me incorporate being transparent about the considered, intended and unintended (when uncovered) negative outcomes – along with an assessment of how likely each is to occur. And how they will be managed. Only when both positive and negative impact is fully disclosed can stakeholders make considered decisions about their next step, and consciously avoid the risk of harming themselves or someone else. They decide if the known, potential harm is outweighed by the overall contribution to well-being.

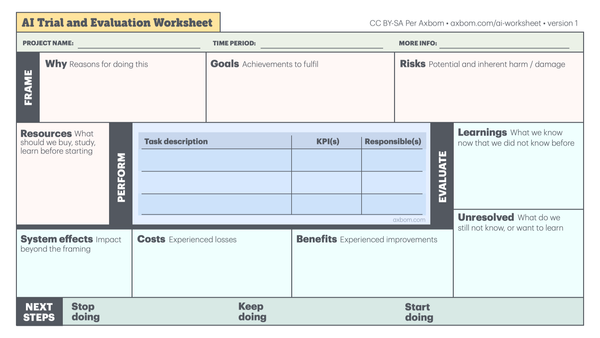

In my Digital Compassion handbook I offer a framework for documenting impact that is based on tools first introduced by Impact Management Project. The idea is to regularly assess potential and real harm with parameters such as:

- Seriousness – how harmful is the impact in relation to other harms

- Contribution – how much is our product design contributing to this negative impact

- Vulnerability – how under-served by society are the people being affected

By regularly researching, assessing and documenting negative impact we have information that allows us to plan and prioritise our work ahead – to minimise or eliminate negative impact where possible. And please note, the answers to these questions are gained from listening to real people from the actual communities, and ideally involving them in both assessment and design work. Best-case, this documentation underpins communication and informed consent.

Of course, a person not interested in adopting a mindset of First, do no harm would find no reason to employ these types of frameworks to help guide their work. And there would be a lack of documentation when evaluating and concluding accountability. Essentially: status quo.

Rather than passively dismiss the oaths of the medical profession it would be fair to see them as an important body of knowledge to learn from. We need to be asking what insights we can can discover and make sense of, not if we can copy and paste. Physicians have been grappling with ethics, and innovating their oaths and codes, before the design community. Not doing that research may in a future be considered design malpractice.

We learn from those who have marched the paths before us and we learn from those who have been harmed. I am confident that if we want to avoid the land mines that are the ethical disasters we are witnessing in tech today, we need better maps. And we need mapmakers who actually live their lives in the disaster areas.

footnote: It really is not the case that all doctors must swear the Hippocratic Oath, as many people believe. In some cases medical schools hold a ceremony where graduating doctors swear some updated version of it. In other schools the Declaration of Geneva physician’s oath is used, or an oath individualised by the institution. The British Medical Association (BMA) drafted a new Hippocratic Oath for consideration by the World Medical Association in 1997 but it was not accepted and there is still not a single modern accepted version. (source: Ideals and the Hippocratic oath [patient.info]).

Sidenote: The Hippocratic Oath matters because it has contributed to common knowledge that physicians need to adhere to certain ethics. We need this awareness among consumers of all the products and designs we contribute to. When people have this knowledge they are in a position to make demands, and are empowered to choose the best possible path for themselves.

See also:

- Swearing to care, a resurgence in medical oaths

- Kim Goodwin’s original thread on Twitter that set me off writing this post.

Further reading about IDEO

In May 2021 George Aye wrote this alarming piece on workplace abuse, power, and manipulation, and struggles with surviving trauma at IDEO:

I will also take this opportunity to share this passage from the The Little Book of IDEO, an outline of the values that IDEO wants to bring forward:

Nobody ever got fired from IDEO for trying, or for being reflective about why something didn’t work out and learning from it. We always encourage people to “ask for forgiveness, not permission,” and we are really lucky that people take this at face value and live it. Let’s be honest, what we do is really hard, we are constantly going into uncharted territory and if we were not trying new things that failed occasionally, we wouldn’t still be in business. When it happens to you, (which it will), own up, take a deep breath, have a glass of wine with your team and try to figure out what you have all learned and how to help others learn from it, so that we can all, well, learn together.

There is a lot to unpack here, and I will leave you to it.

Member discussion