As part of the feedback and reactions to my recent post on the Dangers of Nir Eyal’s books, I received a very relevant question. It relates to how we as designers architect the choices that are available to users, and thereby influence their decision-making. How much of this is really okay? My response turned out quite long and I offer it in a more accessible format here.

The question from Sam Horodezky reads as follows:

Per what do you think about harnessing basic findings about how to frame a problem; for example, if you set as default during employee benefits onboarding to deduct money from the paycheck, it is well known that employees are more likely to save for retirement.

And my response, only slightly revised after my Twitter harangue:

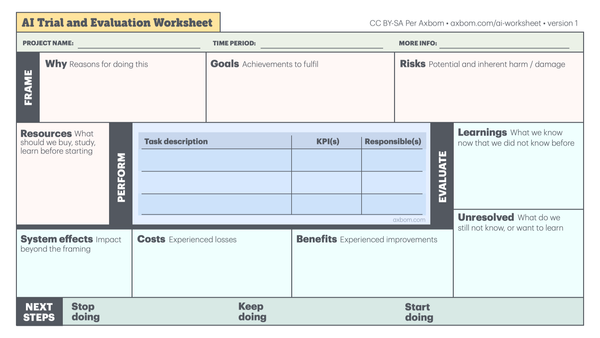

This is an excellent example. There are many ways in which defaults are taught in design as a way to encourage specific behavior. I’m gonna try and break down my process using your example. Bear with me:

First. We are assuming that it is better for employees that we take responsibility for saving for their retirement. To identify risks with this assumption I would run a session asking for situations where this could be considered wrong or harmful.

For example:

- A person is terminally ill and money is of value now but not later.

- A substantial inheritance is known about as a future installment and there is no need for saving.

- The person is more adept at investing and can make money grow faster elsewhere.

Now these scenarios were off the top of my head. But I’m a middle-aged white privileged dude. So this is where it becomes immensely important to bring in people who are experts at understanding risk, because they are themselves always at risk. I don’t fit that profile.

I try to help people understand this in general when I work with usability and accessibility issues. By bringing in those who are experts at seeing how people could get hurt (because they are the people who keep getting sidestepped) we can identify many more risks.

Once we have a list of risks we evaluate the impact of each:

- Who is potentially harmed?

- How vulnerable are they?

- How serious is it?

- How likely is it to happen?

- How much of this effect is our doing?

By mapping out the impact we can get a better understanding of how much sense it makes to ignore a risk or take actions to avoid it. Generally if a person is vulnerable and the effect is serious, that is a stronger case to take action.

Sometimes we won’t be able to find risks that would motivate a change in the assumption, and sometimes we will. By doing the exercise we will feel much better about the decision, and we have documentation to prove our efforts.

But, it doesn’t end there of course. Our assumption now is that we’ve done our due diligence. To disprove that, we have to set mechanisms in place for listening. This exercise or similar needs to be repeated regularly with feedback solicited actively and passively.

One thing I’d add is to not only involve the risk experts but also leadership and other stakeholders. By participating in impact assessment they also feel more ownership of the outcome. And positive impact can be mapped as well to find a sensible balance.

In the end, it’s all about communication. We get a feel for the room and communicate our message. Then we listen. We listen to see if our message is received and understood. And if it benefits the recipient. Or even harms them.

In many projects, products and services people stop listening at one point or another. And that’s when the discovery of harm is left to chance and whatever happens when trust deteriorates. If we’re lucky, people get angry. Worst case they disappear.

Design is a powerful force. And defaults are extremely powerful if we have a large user base. It’s easy to get distracted by that power and miss the many people at the edges of our research. The best we can do as designers is to promise ourselves to not ignore them.

To protect people we have to assume there are weaknesses in our assumptions. By making people aware of our assumptions there is a greater chance they give us something to listen to. If we hide our assumption from them, we are making it rather difficult for them to object.

Addendum:

Your decision on making people aware – or not – of how you have decided to help them, will be a reflection of how much you believe they should be granted autonomy. From case to case this may not be a self-evident decision, but what should be self-evident is that you always set aside the time for reflective reasoning.

Member discussion