In April of 2019 the AI Now Institute of New York University published the research paper DISCRIMINATING SYSTEMS — Gender, Race, and Power in AI. The report concluded that there is a diversity crisis in the AI sector across gender and race. The authors called for an acknowledgement of the great risks of the significant power imbalance. In fact, AI researchers find time and time again that bias in AI reflects historical patterns of discrimination. When this pattern of discrimination keeps repeating itself in the very workforce that calls it out as a problem, it’s time to wake up and call out the bias within the workforce itself.

Providing the most striking and illustrative of examples, less than a month before the research report came out, Stanford launched their Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence. Of 121 faculty members featured on their web page, not a single person was black.

Even a full year before these findings, Timnit Gebru described the core of the problem eloquently, even then referring to a “diversity crisis”, in an interview with MIT Technology Review:

There is a bias to what kinds of problems we think are important, what kinds of research we think are important, and where we think AI should go. If we don’t have diversity in our set of researchers, we are not going to address problems that are faced by the majority of people in the world. When problems don’t affect us, we don’t think they’re that important, and we might not even know what these problems are, because we’re not interacting with the people who are experiencing them.

Timnit Gebru is an Ethiopian computer scientist and the technical co-lead of the Ethical Artificial Intelligence Team at Google. She cofounded the Black in AI community of researchers in 2016 after she attended an artificial intelligence conference and noticed that she was the only black woman out of 8,500 delegates.

While I’m generally not surprised by the systemic discrimination, I am surprised by the lack of self-awareness on display when putting together representative groups within AI. You see, it is quite safe to assume that most AI researchers have read the research paper from the AI Now Institute, that they have been interviewed by newspapers about it and that they stand on stage addressing it. Specialists see the problem, yet often fail to see how they may be part of the problem.

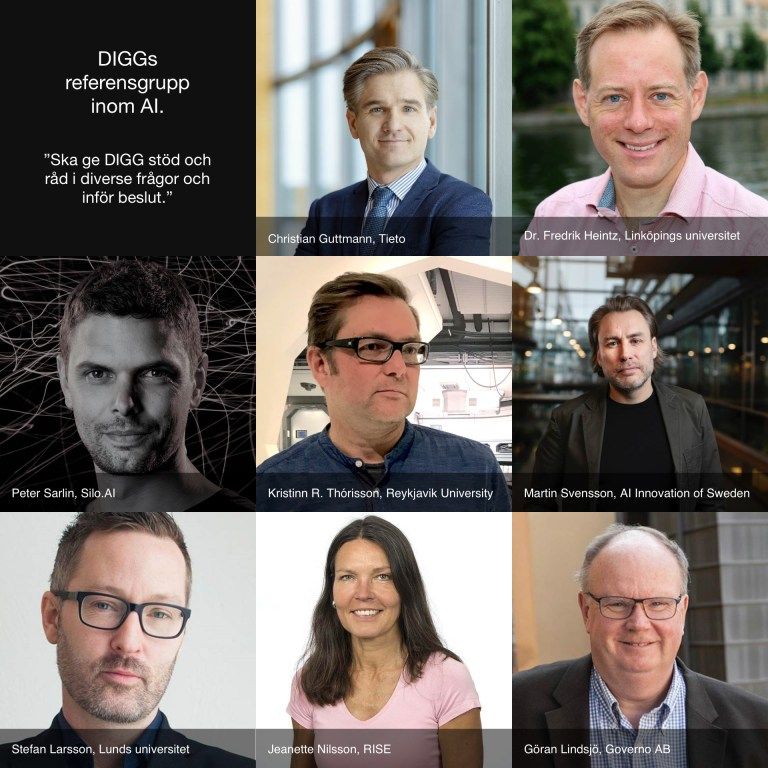

This is why I was especially concerned to see the composition of a new advisory group within the field of AI for Sweden’s government authority for digitalization of the public sector (DIGG). The 8-person team appears to consist of 7 white men and 1 white woman, all around 40 years of age or above. Sweden being one of the world’s most gender-egalitarian countries, this should disappoint.

Of course it doesn’t have to be like this. And shouldn’t. In less than 30 minutes I joined my friend Marcus Österberg in putting together a list of 15 female and/or nonwhite AI experts in Sweden. We obviously shouldn’t stop there, and as many today are pointing out, including Sarah Myers West, Meredith Whittaker and Kate Crawford in their research paper, “a focus on ‘women in tech’ is too narrow and likely to privilege white women over others”. From the report:

We need to acknowledge how the intersections of race, gender, and other identities and attributes shape people’s experiences with AI. The vast majority of AI studies assume gender is binary, and commonly assign people as ‘male’ or ‘female’ based on physical appearance and stereotypical assumptions, erasing all other forms of gender identity.

In the end, the diversity crisis is about power. It affects who benefits from the development of AI-powered tools and services. We need more equitable focus on including under-represented groups. Because if those in power fail to see the issues of vulnerable people, and keep failing to see how representation matters, the issues of the most privileged will ever be the only ones on the agenda.

Don’t miss the reactions to this post below.

Updates

- November 20, 2019: The list of women in AI (Sweden-based) is now online and growing.

- November 20, 2019: I have information that DIGG have revised their advisory group and there are now more women represented. I have yet to see the current composition.

Further reading/listening

- The research paper: AI Now Institute. Discriminating Systems. Gender, Race and Power in AI.

- Understand the problem of bias. Can you make AI fairer than a judge? Play our courtroom algorithm game. an interactive article by Karen Hao.

- “We’re in a diversity crisis”: cofounder of Black in AI on what’s poisoning algorithms in our lives (MIT Technology Review)

- Podcast, CBC Radio: How algorithms create a ‘digital underclass’. Princeton sociologist Ruha Benjamin argues bias is encoded in new tech. Benjamin is also the author of Race After Technology.

- Podcast, Clear+Vivid with Alan Alda. I can really recommend this episode of Clear+Vivid where Alan Alda and his producers speak with some of today’s most outspoken advocates for professional women in the STEM fields. We hear from Melinda Gates, Jo Handelsman, Nancy Hopkins, Hope Jahren, Pardis Sabeti, Leslie Vosshall, and many more. Is There a Revolution for Women In Science? Are Things Finally Changing?

- In Swedish by Marcus Österberg: DIGG:s AI-referensgrupp 88% vita män

Reactions

I've added some reactions to this article that have appeared elsewhere.

I had a great conversation with Lars Höög on Linkedin in relation to the article:

Lars:

The text somehow also tells the story of what different societies see as distinguishing – race in the USA and gender in Sweden.

I couldn’t help but to reflect on that “In less than 30 minutes I [Per] joined my friend Marcus Österberg in putting together a list of 15 female and/or nonwhite AI experts in Sweden.”

No, making one sample (Per picking Marcus) is not significant but when is it? How representative to the research community is the group of eight men and one woman. That they are not representative to the full population is true but what about age, are all geographical parts of Sweden represented, what about people with disabilities, etc?

When is a group representative?

On the main topic, I totally agree that AI research and commercial applications must not repeat the bias from e.g medical and pharmaceutical research in adopting mostly to the western European male population.

Me:

Agree with all of this, which is why it was important for me to end on the note that it’s truly about power.

I also thought of diverging into the complexities of the many people who are excluded, as well as the hundreds of different combinations of visible and invisible disabilities (”non-normal traits”) that are always excluded. But decided against it to make this particular text more readable. 🙂

I would argue that the people who understand risk the least are the people who have experienced the least of it – and those people are often picked to lead. When including people who have been set aside by society and whose voice is rarely listened to, those people will have a greater understanding of the many things that can put various people at risk, and an inclination to search out those risks.

Just so I understand, do you believe the comment about Marcus and I making a quick list detracts from the overall message? My intent here was to counter the argument that there are very few nonwhite males in the industry. But it was also important for me to stress that a list like this is not enough (the very next sentence).

I am of course aware of the irony of two middle-aged men arguing these points but unfortunately my experience is that these points need to be made by us because we still have that systemic power of being listened to. Sooner rather than later I hope that more underserved voices vill be empowered to make these arguments (many already do) and be listened to (today they seldom are).

When is a group representative? My take: When it is obvious that there have been efforts to include a wide variety of people who bring their own unique experiences and skills to the table. But also when this is accompanied by an outspoken tactic of regularly listening to, and communicating with, people who are at risk. Conversely, a group is lacking in representation when it is expected that several people in the group bring very similar experiences and skills to the table.

Yes, I do believe it is possible to end up with a group that is diverse but does not appear diverse. In this scenario it is important to be transparent about why the members have been approached and how their perspectives, and activities, matter and differ.

Also, we can not ignore the negative societal effects of people never seeing someone like them in an advisory position.

Lars:

Maybe it’s commercial interests that form the gravest risk of exclusion, or?

Me:

I think exclusion is caused by unawareness, lack of understanding and segregation. But I also believe people can learn to exercise compassion for people they do not understand or are prejudiced against.

Commercial interests matter, but commercial interests also produce many services that include and help people. If more people demand inclusion, commercial interests will provide them, but for this to happen there must be greater awareness of the exclusion.

If we take people with disabilities as an example, more people with disabilities need to for example feature generally in pop culture, movies and tv, to boost that awareness.

I believe one of my biggest contributions right now can be fighting for awareness.

Lars:

I must object and add perspectives though.

“If more people demand inclusion, commercial interests will provide them” … but only if they add to the bottom line result or positive publicity that can be seen as goodwill to benefit from. It’s spelled C.A.P.I.T.A.L.I.S.M and it really is a suboptimal way of creating ubiquitous value.

“more people with disabilities need to for example feature generally in pop culture, movies and tv, to boost that awareness” is a claim that I do not object to but there is no clear connection from that to avoiding further marginalisation.

An example of the latter from about 20 years ago when I worked in the mobile phone development business and time after time raised the complaint that due to interference between the phones and my hearing aids I could not actually use the products we made. I was awarded for ideas on that but was there any change? No. Why was that? The ratio of potential customers lost was marginal and the cost of research, development and production would likely be higher than the benefit of extra sale.

Me:

Good example. My comment was very simplified, but yes, “demand” in my statement would need to involve either gains (more people buy) or perhaps avoided loss (avoiding loss when people won’t buy from a company they regard as unethical). But I would like to believe there are also companies out there who can define value in more ways than money. I struggle back and forth with the capitalism problem but keep returning to the fact that we must in some way work in unison with capitalism to make change. I responded well to Future of Capitalism by Paul Collier and I try to create awareness around value-driven organizations as profitable. Companies with a purpose beyond profit tend to make more money (Financial Times).

While still mostly paper products, I like where the discussion is heading: 181 Top CEOs Have Realized Companies Need a Purpose Beyond Profit (Harvard Business Review).

Also see further interesting discussions in Swedish on Åsa Holmberg’s LinkedIn post.

In the LinkedIn post by Ninni Udén there is an official response from DIGG(my translation below):

Thank you for your input and engagement in this issue. We can only agree and despite having this issue also raised internally we have been unsuccessful in achieving the right representation for the first meeting. But we are working on a list of candidates and on the first meeting of the advisory group on October 24 we will bring up the issue. The women we have asked have unfortunately chosen to decline or opted to suggest other colleagues in the industry. As with all advisory groups it’s important that the members are a reflection of society at large – the ones we work for. We’re not there yet. We welcome suggestions for suitable candidates, men as well as women.

Member discussion