When I claim that online harassment happens by design I am often met with raised eyebrows. I am not saying that it’s the intent of designers to encourage harassment, but I am saying that it’s what the resulting design is doing. It certainly is doing little to prevent it from happening.

It is strictly not in today’s “corporate interest” to educate people about the risks of using social media. If people were more aware they would perhaps even think more about protecting their data, which is what most social platforms require to make money. I still have hope that corporate interest in the future will, to a greater extent, include the intent to avoid negative impact and also recognize the benefits of maintaining trust and reputation.

We are undoubtedly, however, living in times where positive outcome for business generally trumps any observed negative impact on people and planet.

The more reports I hear about people being targets of harassment on social media, the more intent I become to help designers understand how their design either contributes to people being hurt or shields them from harm.

In a race to simplify, entice and delight — often with the goal to acquire users that can be sold to advertisers — there is very little room left for helping people pause, reflect and make considered choices. Designers generally push, nudge and shove people through a path of low resistance. And should a user later push back and and report annoyances, the response tends to be along the lines of “You should have known what you were getting yourself into.”

But how could anyone possibly know what they are getting themselves into when a common premise is that social platforms are offering something new and unique? Is it the fault of individuals that do not read terms of service that they are tracked, data-mined and name-called? That they are subjected to wildly inaccurate news reports? The creator of the web himself, Tim Berners-Lee, readily deems it “humanly impossible” for people to read terms of service. And studies confirm that for anyone to read the privacy policies of all the sites and services they use online in a year would take over 72 working days.

The stance that people should be more aware and take more responsibility for their actions online is often echoed by organizations unwilling to assume ownership of an online-related problem. After all, they only designed the service and made it easy.

Let me give some examples of how it would be possible to help people become more aware, avoid being harmed and protect their own interests. Please note that these are things designers could be doing but are currently choosing not to do.

1. Teach in context

Sharing photos online is a no-brainer. It is second nature to most online citizens. For many it is arguably the primary incentive for participating on the Internet. Yet few services will tell us what data a photo contains, what data they collect from the photos, and how it could be accessed by others — my obvious example being GPS location tags contained in the metadata of mobile snapshots.

What if the first time I upload or send a photo with GPS metadata my social media service tells me exactly what they do with it. Because frankly, a vast majority of people are simply unaware the data even exists.

It would go something like this:

- I select and upload a photo.

- A message is displayed telling me “This photo contains map coordinates of the location the photo was taken. Our service will strip this information from the photo so that it is unavailable to others on platform X. Location information will be saved in our database so that we may provide more relevant ads for you.

- The user would then be able to respond with a selection of options, such as “OK” / “Cancel upload” / “Tell me more” / “Change privacy settings”.

Simple as that. The point is not the exact solution that I came up with on the fly here, though. The important thing is that it is an example of choosing to educate inline and in context, as people are more likely to remember and understand something when they are taking the action and not when reading five pages of privacy policy the month before (which we already know they also won’t even attempt).

The reality of what tends to happen on social platforms today, of course, is that people are encouraged — without warning — to add location to photo posts even when there are no tags available.

2. Allow incremental deblurring of potentially harmful content

Unsolicited dick pics are a societal issue. It is something many women are exposed to on a daily or weekly basis.

So how could I as a designer protect more women from being abused by these photos?

Well, let’s play with the idea of incremental deblurring. I receive a picture and it is blurred. The blur will allow me to, with some degree of confidence, identify if it is a picture that I do want to view in full resolution. To deblur the photo I would have to tap on it. The idea could be that we would tap on it several times to deblur it incrementally, allowing me with greater confidence to decide if it is something I want to avoid seeing more of.

Other potential options available in this scenario could be along the lines of “Approve all images from this sender”, “Block” and “Block and report”.

There is absolutely no reason to design in such a way that people are immediately exposed to a high resolution image from someone they have not approved as a trustworthy person to send them images. Especially now that we as designers are aware of the dilemma of dick pics and the negative impact it is having.

There are other ways to approach this issue. In fact, there are algorithms that can auto-detect and flag potential dick pics with a high degree of accuracy.

Again, the important point here is that we need to be having these conversations about choosing design that protects rather than harms.

3. Provide reminders and time-outs for people to manage sensitive and intrusive content

It will still happen that I notice I am logged in on certain services on devices I haven’t used in years. Very little is done to help me stay aware of where my behavior is tracked. Location sharing is awesome but does it really benefit me to have it on all the time? Notifications for events can be great (or awful) but do I really want to keep getting notifications for a discussion happening a year after the fact?

Several design solutions come to mind:

- Remind me once a month on what devices I am logged in.

- Allow me to share my location on a time-limit of 1 hour up to 2 weeks, but then turn it off and allow me to reactivate.

- Notifications likewise do not require the binary characteristics that are imposed on them today: on or off. Let them be on for a limited period of time so that I may re-evaluate. Maybe even let me choose between real-time or a batch notification on a specific time of day.

The idea that people should turn something on and leave it on indefinitely aligns well with the design decision to relentlessly promote, push and nudge for the setting that is better for the business. Very little is done to promote a design that will allow individuals to confidently and carefully choose what is best for their situation.

Have you noticed that when you have notifications turned off you are regularly reminded to turn them on? Have you noticed that when you have notifications turned on you are never reminded that you may want to turn them off?

Designers of these solutions are clearly looking at the bottom line, at conversion rates and time-on-site. But rarely are they looking out for the true interests of the individual they often claim to be helping.

Many readers will still be thinking: “Social media platforms don’t harass people; people harass people”. Honestly, I believe social media platforms are doing a wonderful job of exposing behavior that has been going on throughout human history. But if we as designers choose to not recognize and address maleficent behavior when we see it happening, we are in fact designing to empower and sustain harassment and exploitation.

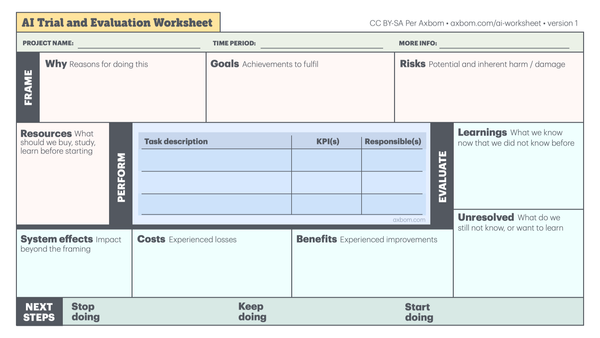

To combat this plague of misguided design we need to consciously add new tools and thinking into the design process. Our mode of work must regularly be looking at, evaluating and responding to how people are being affected when using the services we are responsible for designing. Failing this we will undoubtedly also fail to work in a way that in any sense of the phrase can be considered human-centric.

Member discussion