The date was September 26, 1983. I was nine years old. Stanislav Petrov was 44 years old. Around my age today. He was working his second straight shift in the control room of the Soviet nuclear early-warning system Oko. Suddenly came what was the greatest fear of the cold war, an alert signalling a nuclear attack from the United States. The system announced that five missiles were headed towards the Soviet Union.

It was now Petrov’s job to forward this information to allow the Soviet Union to commence their counterattack. But Petrov never did. He himself decided to report this alert as a false alarm instead of letting former KGB-leader Yuri Andropov determine the world’s fate. In interviews, Petrov pointed out that he thought it was unlikely to be a nuclear attack with only five missiles. There should have been more. In 2013, he pointed out that his civilian education was crucial. His military colleagues would surely have reported an act of war.

Many experts have acknowledged that a good part of the world’s population has Petrov to thank for their lives. The significance of his act was of course that he as a human dared question the computerized system. A computer system that, in this case, had misinterpreted an unusual weather phenomenon.

Love of Reading

When these events unfolded I was nine years old and attending an American school in Saudi Arabia. I loved books. Which is why I also loved learning about the Dewey Decimal System, the most common taxonomy used in libraries around the world to categorize books in subject areas. In large chests with small drawers I found small cards with categories that helped me find new, exciting books. The categories encompass the digits 1 to 1000, frequently with decimal places to include specialist areas. Hence decimal system.

This means that all the world’s subject areas are divided up into ten main groups. Everything from computer science to geography and history.

For example, books concerning religion are placed within the numbers 200-299. In an overtly unbalanced configuration, however, Christianity is assigned categories 200-289, while the rest of the world’s religions coexist in the remaining ten main categories: 290-299.

When I was nine years old , the subject of homosexuality was in category 301,424, studies of gender in society. In 1989, it was also placed in 363.49, social problems. But many books of course for a long timed also retained their former categories from 1932 when homosexuality was placed in categories 132, mental disorders, and 159.9, abnormal psychology .

Changing values

Books that dealt with homosexuality were, to say the least, controversial in 1932. In Nazi Germany, starting in 1933, book-burning commenced of all books that in some way had content of a homosexual nature. Homosexuals in the secret state police, the Gestapo, were murdered. And between 1933 and 1945 homosexuals around the country were imprisoned. Of those who then also ended up in concentration camps, scientists estimate that 60% were executed. Many were also victims of medical experiments in which cures for homosexuality was sought.

Something that haunted historians for many years was how the Third Reich so effectively was able to map, find, terrorize and execute homosexuals, Jews, Roma, people with disabilities and people who ended up in the category ‘anti-social’.

Today we know that the answer to that question is automation.

The man on the left in this picture is Adolf Hitler, the man who came to power in connection with the book burning. The man sitting on Hitler’s left side is Thomas J. Watson, leader of IBM during the years 1914 to 1956.

Automation of terror

Transporting more than six million people from their homes to ghettos and then from the ghettos to concentration camps and gas chambers is an unfathomable horror, and startling as a logistical feasibility.

Beginning already in 1933, IBM’s exclusive punch card technology was used to categorize and streamline Hitler’s plan: Final Solution to the Jewish Question. After the release of archived documents in 2012, we know that the punch cards, machines, training and servicing were all controlled from IBM’s headquarters in New York and later through subsidiaries in Germany.

This is a picture of one of the many machines that were built and deployed for the purpose. They were used to manage food rationing for the purpose of starving prisoners, for the timetables of the many trains, but also for the categorization of people.

The 2012 documents revealed some of the codes of the concentration camps and numbers used to codify people. Number 3 for Homosexual, 8 for Jew, 9 for Anti-social, and number 12 for ‘gypsies’. There were also codes that categorized how people died, or as was more often the case: executed. Special treatment was the euphemism for gas chamber.

Thomas J. Watson is, in many people’s eyes, an admirable businessman who contributed to building IBM into a wealthy and profitable global company and world leader in tech. He was one of the richest men of the time and was called the world’s best salesman. Many listen to his advice. Knowing now what his company actively and knowingly contributed to, many of his statements today come off as repugnant:

“Doing business is a game, the greatest game in the world if you know how to play it.”

It is also telling that when details about IBM’s role during the Holocaust have leaked out the company’s defense, even in recent years, has built very much on the premise :

“We are just a technology company.”

Even more strikingly tone-deaf in light of corporate history and responsibility, IBM’s renowned artificial intelligence platform today bears his name and their 2019 campaign proudly proclaims that you now can have “Watson anywhere“. It’s designed to “help companies uncover previously unobtainable insights from their data”.

Classification of people

Categorization, labelling and grading of people and information is a tool we naturally use to manage the impossible complexity of the environments and contexts we as humans are trying to understand. It is extremely effective, but also contributes to some of the deepest problems we are facing.

As late as 2016, there have been studies performed to show how criminals can be identifiedmerely with the aid of facial proportions. This is a form of phrenology – determining behavior based on head shape – I’m sure many assumed that the research community had abandoned. And now just last Sunday, on the 24th of November 2019, we learned how China is operating citizen arrests based on algorithms, thanks to the so-called China Cables leak. In June 2017, more than 24,000 names were flagged as “suspect” by an algoritm, and in one week Xinjiang security personnel found 15,683 of these people and placed them in detention camps.

Earlier in May of this year we learned from experiments with facial recognition in England, attempting to track criminals, how the system for face recognition was wrong in 96% of cases. And, of course, facial recognition is most often wrong when it comes to non-white people. The Independent article describes the case of a 14-year old schoolboy who had to submit fingerprints due to one of the many misidentifications.

But we don’t always have to go as far as automation and AI to find examples of people experiencing harm. Now that we are digitizing all types of school systems and relying on them for communication and reporting, issues like this appear:

“My transgender student’s legal name is showing on our online discussion board. How can I keep him from being outed to his classmates?”

Of course, most digital school platforms do not allow neither student nor teacher to change their name. Many digital systems, often also public ones, fail at the most basic levels of protecting privacy and integrity.

Homosexuality is still illegal in 70 countries. Sentencing can often lead to several years in prison. In a handful of countries, the death penalty is used.

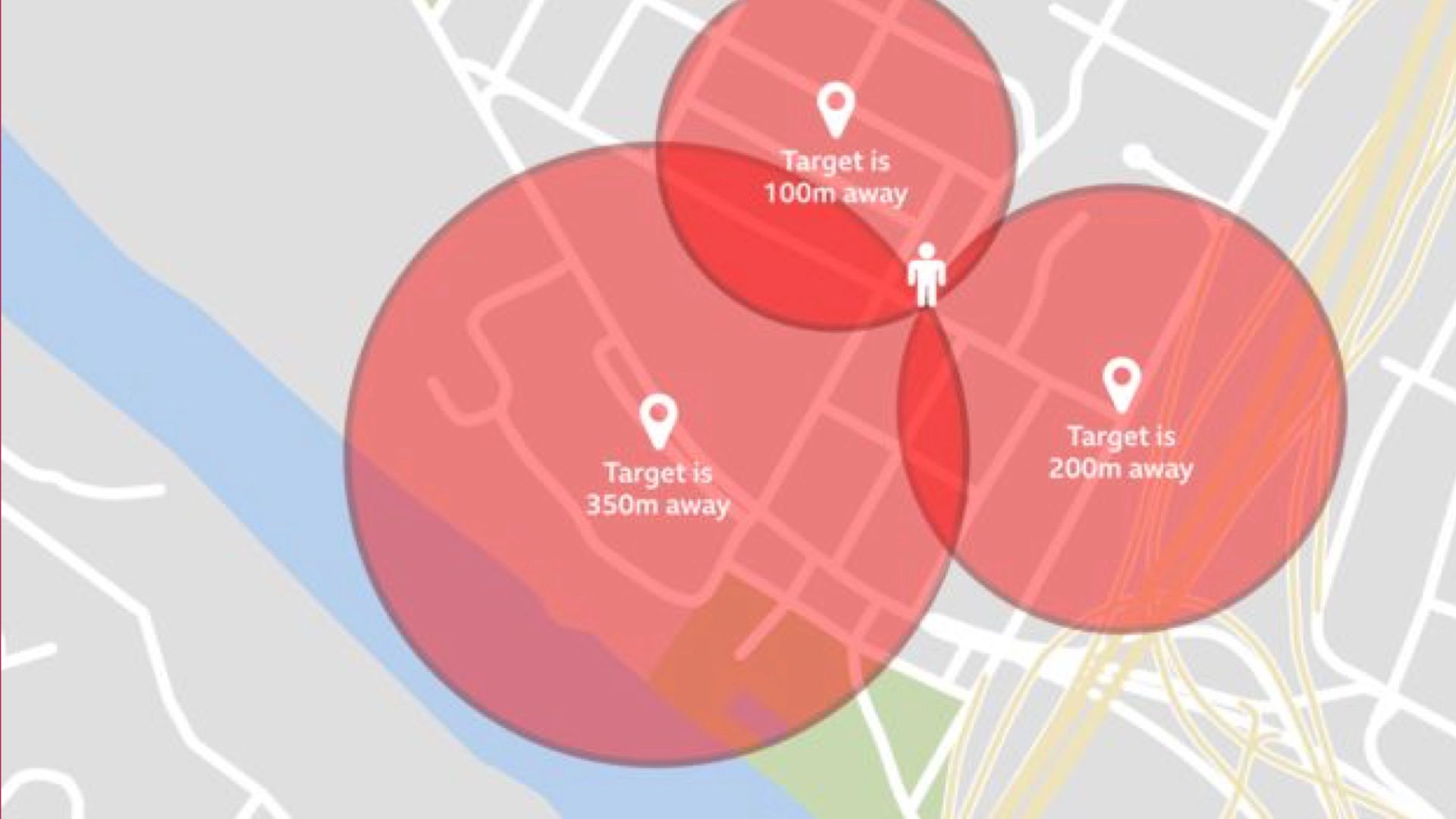

That’s one reason to be concerned when dating apps display distance to other online users. Something that many surely forget to turn off when traveling. But at least they only display distance, you may be thinking. They do not show direction .

Indeed, the only thing required to pinpoint an almost exact location of a person is manual triangulation. Stand in three different places and make a circle around each place with the given distance as the radius. Where these three circles intersect is the where you will find the anonymous individual.

This triangulation can be done by a person who stands in three different places, or of course even faster by three people carrying baseball bats who are working together .

Apps designed to improve people’s lives are exposing their own target groups to danger. And the people at risk have often not been informed about these risks in a satisfactory way. There are now for example reports coming out on police in Egypt using dating apps to entrap suspected homosexual men.

The processes do not make a stand

When we hear about technology where people are harmed, the stories often have something in common. It is those with a disregarded voice and who are discriminated – people already served badly by society – who are the most vulnerable. People who are already favored by society often have a good relationship with technology and can see and appreciate how it improves their everyday life and well-being.

What has become clear in my research on ethics and design, when trying to understand why people are harmed again and again, is that methods and processes keep revealing themselves as a contributing factor. Nothing in our processes is systematically taking into account and mitigating negative impact on human beings.

In recent years, concepts such as agile and lean have become commonplace for organizations and companies. Incremental and iterative development methods are all over the workplace. These methods contribute to value-creation through frequent feedback loops involving the buyers of products and services. This increases the probability of making something they are happy with.

In a frequently used illustration of an agile process, created by the swede Henrik Kniberg, the first item built is a skateboard. This is shown and tested with target groups, and in the next iteration (development cycle) becomes a scooter, or kickbike. The circular feedback then leads to the development of a bicycle, a motorcycle and a finally a car. But the point is that you did not beforehand understand that you were building a car. The iterative process brought you there.

The right way is not always the right thing

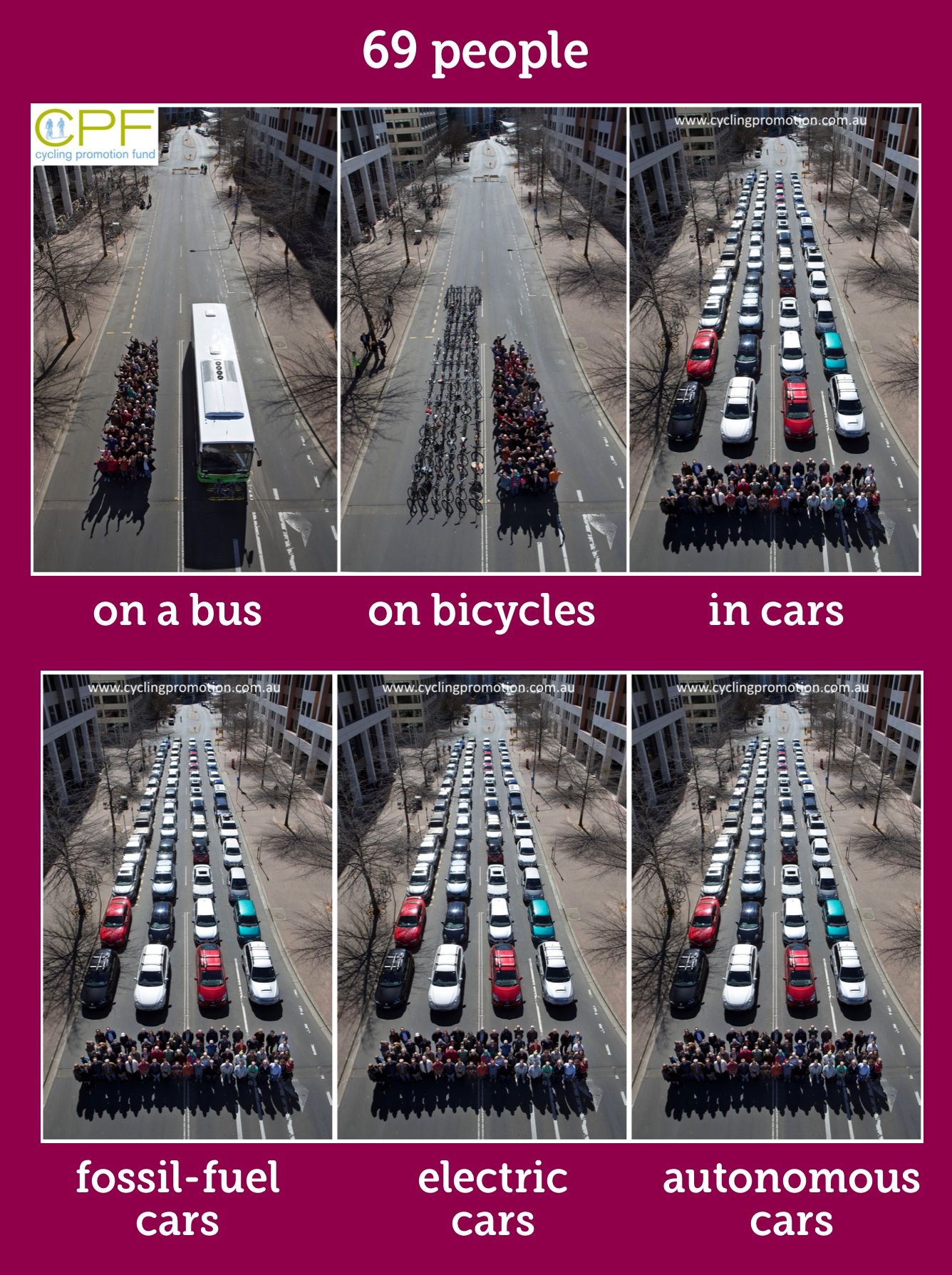

I am a believer in the usefulness of agile methodologies as a more resource-efficient way of working out and solving the problems of a target group. But they do not prevent solutions that also contribute to congestion, accidents, pollution, exhaust fumes or other ways of endangering people.

Because even if we keep getting better at building things the right way, and can reach further and affect more people, we have yet to adopt the methods that allow us to build the right thing — which involves actively working towards minimising negative impact.

To exemplify I often show this famous Australian image that illustrates how much road space is taken up by 69 people in a bus, on bicycles and finally: in cars. The cars, despite there not being one car per person, by far require the most space. The most innovative companies are praised when they respond with the launch of electric cars and autonomous cars. These vehicles, of course, take up exactly the same amount of road space as fossil-fueled cars. Worryingly there is also no indication that they lower the number of cars on the road. Money controls the direction of innovation, and impact on well-being is rarely gauged as a success factor .

To emphasize my point about who is harmed, and while we’re on the topic of transportation, last Wednesday I took these two pictures in Stockholm. While it may seem that one of these scooters (the one lying down) is a greater obstacle than the other (parked on the sidewalk) this interpretation is one based in privilege.

The truth is of course that both these scooters represent an equally troublesome obstacle for people who are visually impaired, or use a wheelchair. People with these temporary or permanent disabilities need to find a safe way to navigate around the scooter to continue their journey.

When you move around a big city with this realization it becomes devastatingly obvious how the onslaught of electric scooters are creating an everyday randomized, and often dangerous, obstacle course for vulnerable people who have previously found comfort in using the same mostly obstacle-free and safe path for decades.

Invisible people

The most dangerous thing about hostile design is when it starts to become invisible for the majority of people. Hostile design is when someone builds products and services that actively excludes and impairs well-being for specific people.

For example, hostile architecture is something that many can discover in their everyday lives. This is when we see spikes on the ledges that could otherwise be used for seating, or more subtly, armrests in the middle of benches so they are not suitable for lying down on. Eventually, this design also becomes completely invisible — by normalization, or by design.

In this example, a solar charger for mobile devices has been installed on a park bench. The solar charger is mounted in the middle of the bench and the component rises well above the seating area. Again, we have the design of a bench impossible to lie down on if you have that temporary need.

Some people are completely excluded, in an invisible way, and thus erased from our consciousness. They themselves already have too weak of a voice to be heard in protest. And because the hostility is not at all apparent – and the majority actually benefit from the solution – there are ever fewer people who protest on their behalf.

In our everyday life this plays out with people who do not get invited to parties when they don’t have the right social media account, people who struggle to apply for jobs in digital platforms, people who can not pay for parking or parents who have difficulty retrieving important information about their children from complicated school platforms. Often these same people had no trouble with the same tasks in their pre-digital versions.

For many their whole community has become akin to visiting someone else’s home and attempting to understand how the television and stovetop works.

Best case they have a relative who can help them.

Design discriminates

To my personal disappointment I learned a few years ago how even the design methodology I worked with for many years is, in essence, discriminatory.

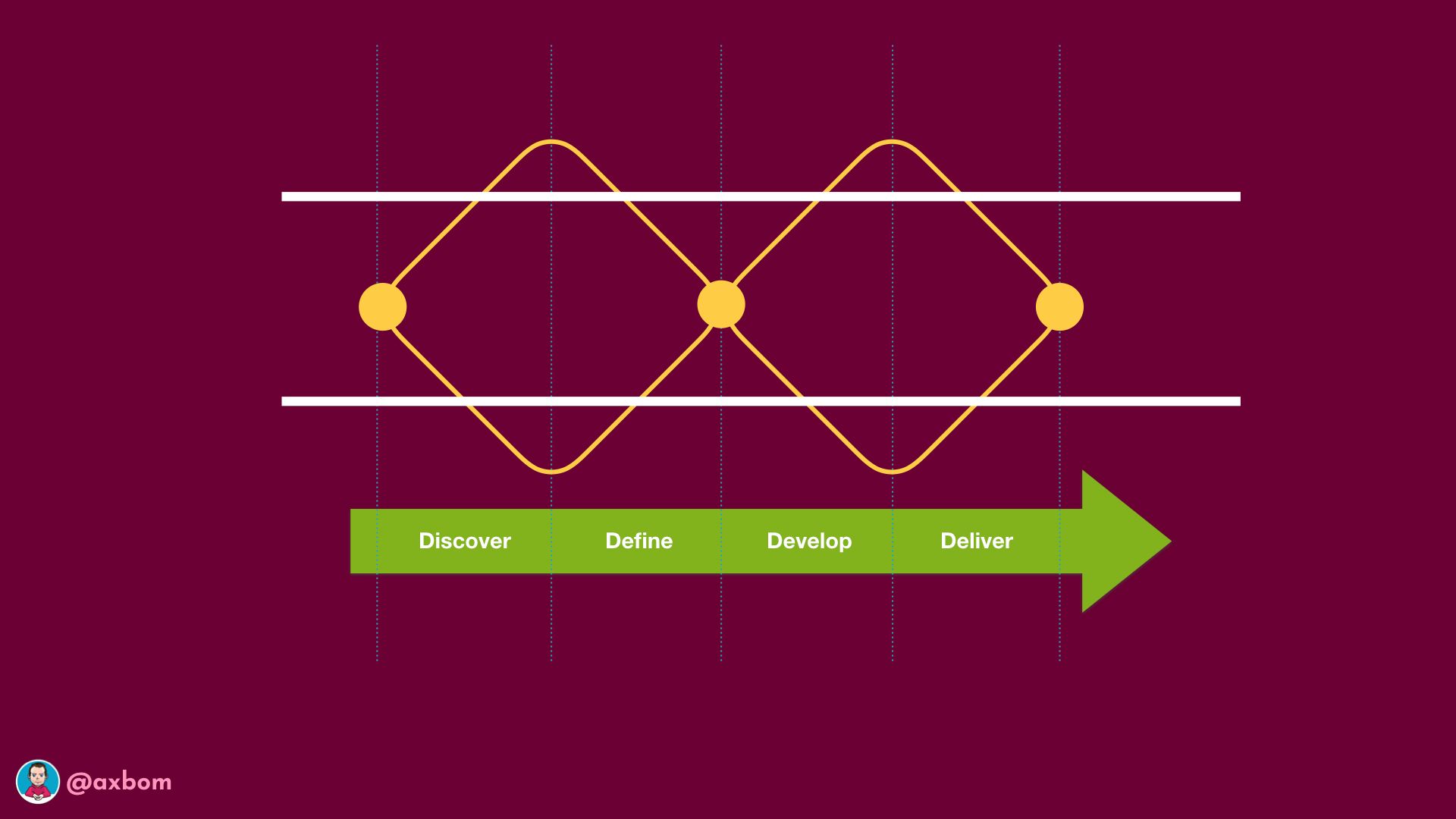

In what is popularly called the “double diamond”, the process diagram illustrates how we put effort into understanding a problem and the related human needs broadly. But as time moves on we need to decide what needs are prioritized.

And that’s when we methodologically choose to focus on the needs that most people have. What many people have in common. Those are the clearest patterns.

The result is that people in the outskirts of the research, and in the outskirts of what can be described as general needs, quite simply are not allowed any consideration in the design solution. There is even a term in the industry for this: edge-case. If you are an edge-case you are not a person whose need is a priority.

If we built with people’s well-being in focus from the start, accessibility for people with disabilities would never be something that came into consideration later in a project, as an add-on. An edge-case would be assessed on the basis of the harm we incur a human being, not based on how rare the event is.

But today most designs prioritize the needs of those already favored by society – who fit in and are normalized – and who benefit doubly because precisely their needs end up in the spotlight.

Measurement increases visibility

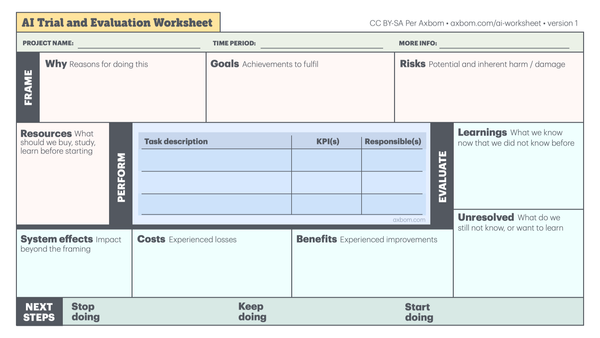

In order to be able to work ethically, in the sense that we avoid building that which causes harm, human well-being must be a part of decision-making. We must put effort into documenting, measuring and imagining how people suffer harm.

This information is then used for:

- expressing clear motives in decision-making

- making visible the people who are otherwise not seen or heard

- prioritizing choices in technological development

- understanding when you should walk back a decision after understanding consequences

- creating traceability (documentation) for ethical choices and considerations

(See Tim Berners – Lee and ContractForTheWeb.Org )

We will never be able to predict everything. But when our methods do not even encourage us to talk about them, negative impact is almost guaranteed. We can always improve our understanding of who is harmed the most and what impact we ourselves wish to contribute to.

Here are two methods :

Impact mapping

Impact mapping is a form of risk analysis concerned with anyone who is affected and what happens to them. Each impact (what happens to who) is then estimated according to four factors :

- How severe is this impact?

Are we talking embarrassment or life and death? - How much do we contribute?

That is to say, if we had not done anything, would this impact exist? The more we contribute, the more it is our responsibility to minimize the negative impact. - How neglected/vulnerable are those affected?

If those affected already have a weak voice in society it’s ever more important to help them strengthen their voices. - How likely is it this to happen?

The higher the probability of the “what” happening, in combination with other factors, the more important it is to take action.

Every assessment is done in a group setting and these factors are estimated and updated as we learn more over time. Best-case, of-course, people with first-hand experience of similar effects are brought in to contribute.

Impact mapping can be a powerful tool as it can be used for both positive and negative effects. Its strength as a tool is that it can help a product development team prioritize not only based on financial outcomes and conversion, but also on the basis of who is harmed and how much.

Use the method to help your organization understand impact, and prioritize activities .

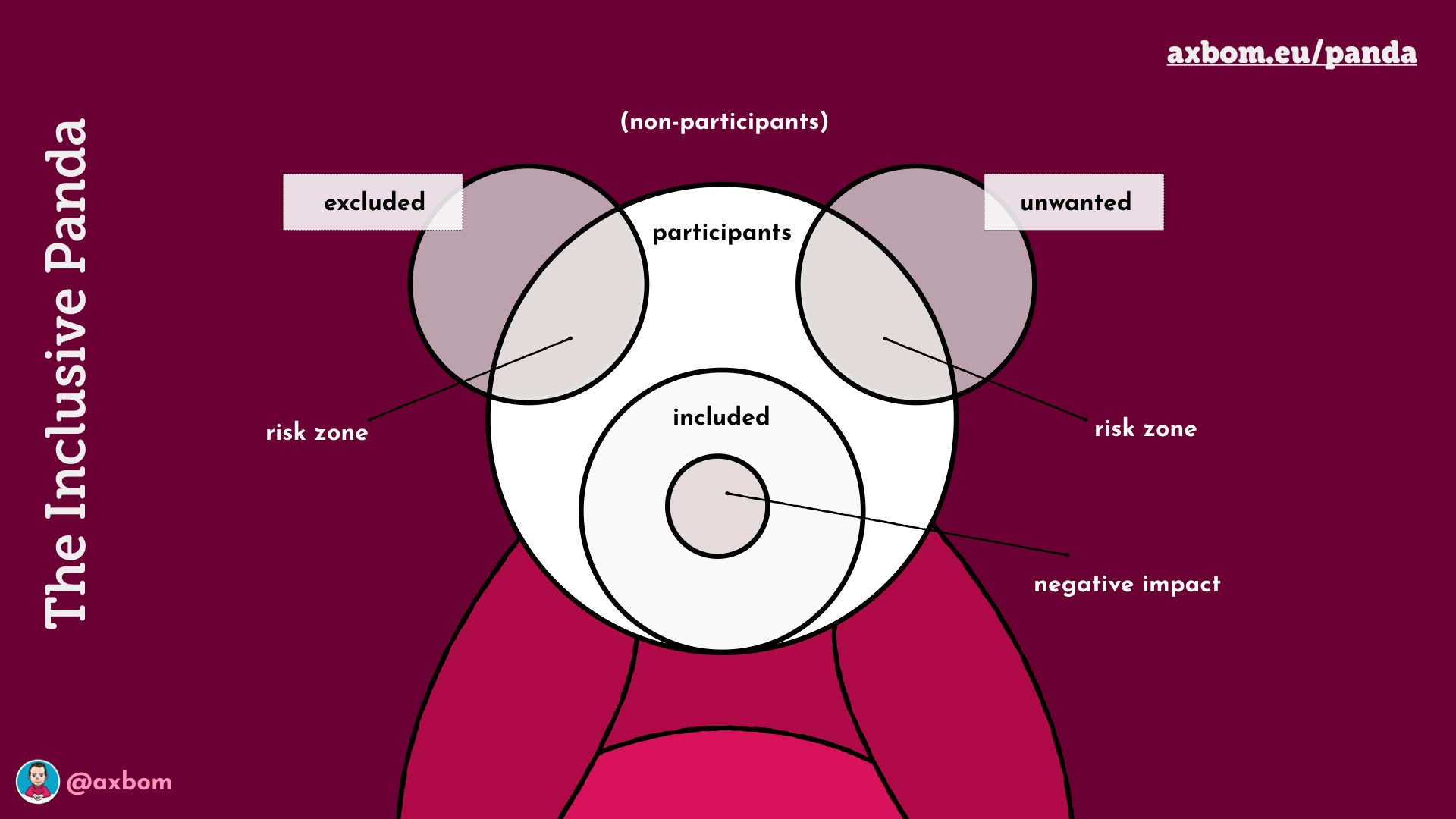

The Inclusive Panda

The panda is a gateway for an organization to more easily understand all the people who can be affected by a digital solution.

The circle in the middle, the muzzle (or snout), encompasses all those we have in mind as our target audience, those we consciously and actively build for.

The ear to the left represents the excluded people. This may be people who would benefit from the solution but no energy is put into building in a way that accomodates their access needs. This could also be people who are not at all favored by the solution but rather directly disadvantaged by it, as in the case of the electric scooters.

The ear to the right represents the unwanted. We do not want these people to use the solution, either because they can harm themselves or because they can damage others. The simplest example is that some solutions for adults should exclude children. And some solutions for children should exclude adults.

The ears overlap with the head to illustrate that there are likely people in both the exluded and unwanted groups who manage to start using all our parts of a solution anyway.

Which allows us to finish on the nose, the segment of those people we build for who are harmed despite our efforts. Either they are harmed by the behavior of unwanted users or you fail to understand their needs and vulnerabilities. Dating apps showing distances to the nearest online users is a good example.

When you regularly map participants and non-participants using The Inclusive Panda you begin to understand the effects on many more people beyond your expected audience. You gain important insights about how your product or service is bigger than the people you are directing your efforts at.

A human act

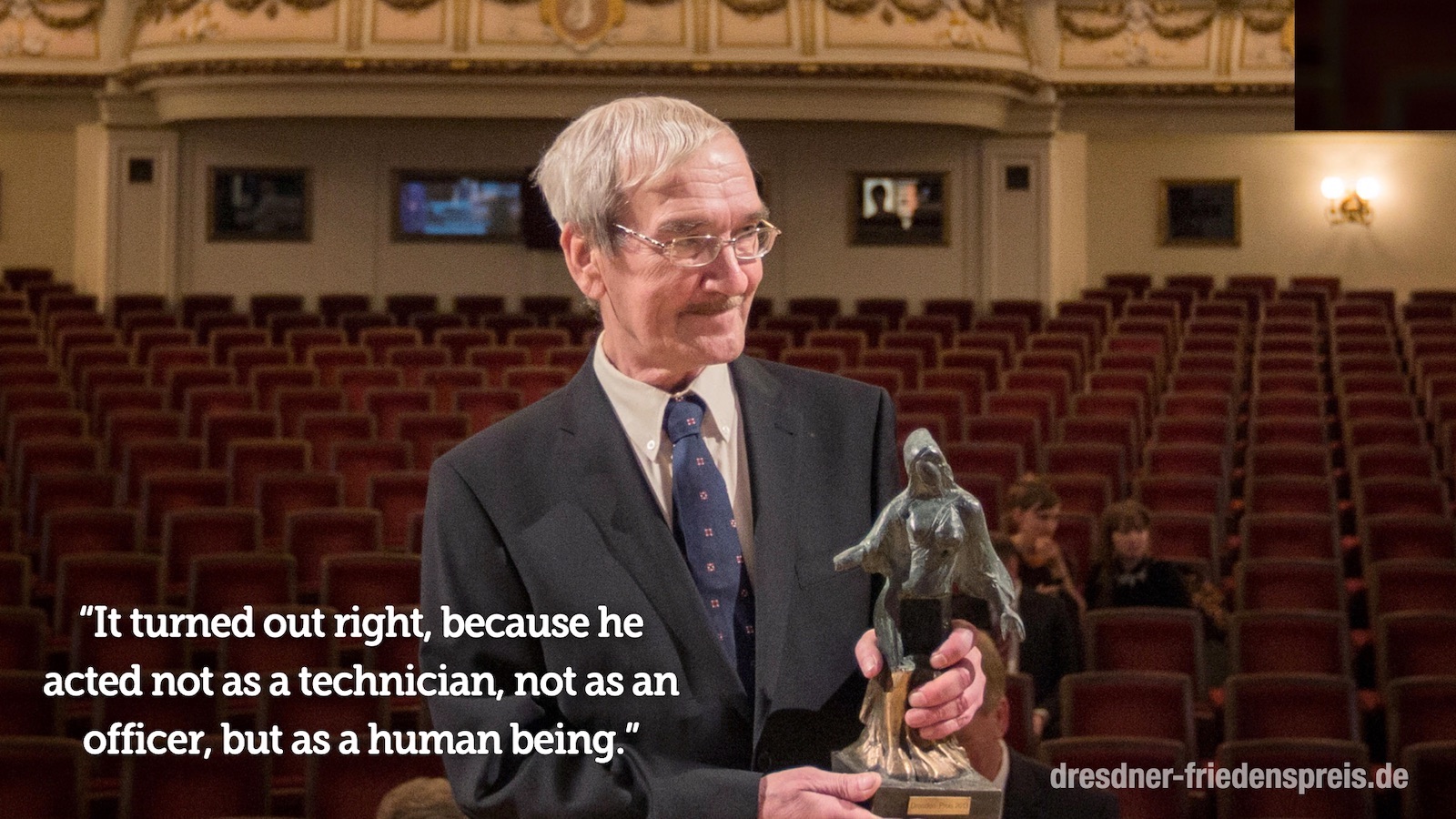

When Stanislav Petrov was awarded the international peace prize Dresdner-Preis in 2013, for his actions in preventing a third world war, the jury expressed the following sentiment:

“It turned out right, because he acted not as technician, not as an officer, but as a human being.”

Stanislav Petrov passed away invisibly in May of 2017. But for anyone out there wishing to act as a human being, you can follow his lead:

- Dare to object when technology assumes the role of decision-maker

- Dare to question the historical data, and classifications, that our information systems and libraries keep alive

- Understand that everything that can be built should not be built, no matter how profitable it is

- Avoid classification of people, but do talk about capabilities and invisibility

- Make visible when people are harmed

- Stand up for making human well-being a central part of any technological development, and one that is measured alongside profitability

This is also why I would like to finish on a hopeful quote from young girl who wrote the following in her diary when she was 14 years old, as a strong reminder to us all:

“How wonderful it is that nobody need wait a single moment before starting to improve the world.”

– Anne Frank

This article is also available in Swedish: Digital omtanke: en mänsklig handling.

Thank you for sharing this post with your friends and colleagues. This article wants to travel.

Further reading

- Stanislav Petrov – Wikipedia

- ‘How I stopped nuclear war’ (BBC)

- Stanislav Petrov saved more lives than just about any human who ever lived – Vox

- Stanislav Petrov, ‘The Man Who Saved The World,’ Dies At 77

- Dewey Decimal Classification – Wikipedia

- IBM & “Death’s Calculator”

- IBM’s Role in the Holocaust – What the new documents reveal

- IBM And Nazi Germany – CBS News

- Neural Network Learns to Identify Criminals by Their Faces – MIT Technology Review

- Exposed: China’s Operating Manuals For Mass Internment And Arrest By Algorithm

- Facial recognition wrongly identifies public as potential criminals 96% of time, figures reveal | The Independent

- Trans-inclusive Design – A List Apart

- Gay dating apps still leaking location data – BBC News

- Dating apps are refuges for Egypt’s LGBTQ community, but they can also be a trap – The Verge

- The Canberra Transport Photo

- Homepage – Contract for the Web

- Introducing the Inclusive Panda • axbom.blog

- AI ethics is all about power

Thanks

- Thanks to Rumman Chowdhury who reminded me of Stanislav Petrov in this brilliant piece: The pitfalls of a “retrofit human” in AI systems.

- Thanks to Aral Balkan who made me aware of IBM’s role in the holocaust and sent me down that terrifying rabbit hole.

- Thanks to Alastair Somerville who first pointed out the obvious faults in the double diamond, elaborated on in his article: How do we design for divergence and diversity if convergence is the goal?

- Thanks to my oldest son who started reading The Diary of a Young Girl. The constant presence of the book in our living room had me keeping Anne Frank top of mind as I was working on the presentation.

- And thanks for all the fantastic feedback on the Swedish presentation and post. This encouraged me to translate it all to English.

Member discussion